The Review: Broadway’s Boys in the Band

By Ross

The stars have come out to party, birthday-wise, at the Booth Theatre on Broadway arranging themselves on that stage around a candle topped cake, ready to play a mean-spirited parlor game of sorts. With a cast of the Out Who’s Who signing up for this band of gay men, the excitement level is high, and it’s no wonder. Boys in the Band is a classic icon of a play, written by Mart Crowley (A Breeze from the Gulf) premiering Off-Broadway in April 14th, 1968 at Theater Four. The play received rave reviews, and ran for a total of 1,001 performances. It revolves around a group of gay men who gather for a birthday party held in Michael’s New York City apartment, taking its title from a line in A Star is Born when James Mason tells a distraught Judy Garland, “You’re singing for yourself and the boys in the band.” That line signifies much in this play, and what has basically been the political gay movement stance for decades much like Harvey Milk and his theatrical campaign of coming out to the people around you. Boys and the Band was groundbreaking, portraying a gay life that was yet to be seen so clearly and unapologetically on stage. The world at the time of this play’s writing did not accept these gentleman and their lifestyle, proclaiming such untruths like what Alan McCarthy, the unexpected party guest says to his host and former college roommate, that he doesn’t care as long as ‘it’ is kept private and not shoved in his face. Today that slogan is sometimes said, especially in our tense political world of Republican lies and con jobs. Some accept that. But we clearly know what that means, and it ain’t good. That statement has nothing to do with loving. Or openness. Or accepting. It’s homophobia pure and simple, wrapped up in a false public relations spin, and is really and truly a threat and a lie, telling us all to step back into the closet, or else.

It was a brave act of courage writing this play back in the late 1950’s. At the time, Crowley was working on a number of television projects in Hollywood before meeting the woman who would help make this play a possibility. Natalie Wood, after meeting Crowley on the set of her film Splendor in the Grass, hired him as her assistant. She held strong convictions and sympathies to the Hollywood gay scene, and help create a way to financially support the writer while giving him plenty of spare time to work on this gay-themed play. According to Crowley in an interview with Sherry Lucas for Mississippi Today, (March 24, 2018), his motivation in writing the play was not particularly born out of activism, but more igniting from a place of anger that “had partially to do with myself and my career, but it also had to do with the social attitude of people around me, and the laws of the day.” As directed by Joe Montello (Broadway’s Three Tall Women), that anger flies at us in this 50th anniversary production, punching us as hard as it can, taking no prisoners in this game of telephone calls. He and this marvelously authentic cast makes us sit up and take notice of these boys, and the band they all play for.

In the 1995 documentary, The Celluloid Closet, Crowley explained, “The self-deprecating humor was born out of a low self-esteem, from a sense of what the times told you about yourself.” Much like Andrew Garfield’s turn as Prior in the current revival of Angels in America, the front is protective, used as a deflective tool against the world and its hatred. Michael, as portrayed strongly by the surprising Jim Parsons (Broadway’s An Act of God, The Normal Heart) breaths fire in and out with this highly volatile brand of self-deprecating wit. It’s like his second bullet-proof skin or layer of armor used to keep the world out, just as much as his fancy sweaters make him feel safe and sound in his very pink apartment. One by the one the guests start to arrive for his best friend’s birthday party. The first is the gorgeously depressed Donald, played stunningly by the stunning Broadway virgin, Matt Bomer (“American Horror Story: Hotel“). The two set the mood exquisitely with their casual barb-laden banter, filling the air within the marvelously designed set and costumes by the incredibly talented David Zinn (Broadway’s SpongeBob SquarePants) with subtly perfect lighting by Hugh Vanstone (Matilda) and sound by Leon Rothenberg (A Doll’s House, Part 2). Everything about this, including the ripe and engaging performances remind us of the 1968 time period without beating us over the head with it. It’s a compelling mixed cocktail of 60’s and modernist, stirred for the upmost relevance and flavor, and a strongly orchestrated statement to all.

But then the phone rings, and instead of it being one of the five guests who are still on their way, it is the very upset Alan, Michael’s straight and married college friend, played solidly by Brian Hutchison (Broadway’s Looped). Crying on the other end of the line, Alan basically pleads with Michael to let him come over that very night. It sounds like he has a confession to make, but to what order is the question. Against his better judgement, Michael gives in, telling him he is welcome, even though the anxiety of what will be seen and revealed to his old friend is almost enough to make a sober man drink.

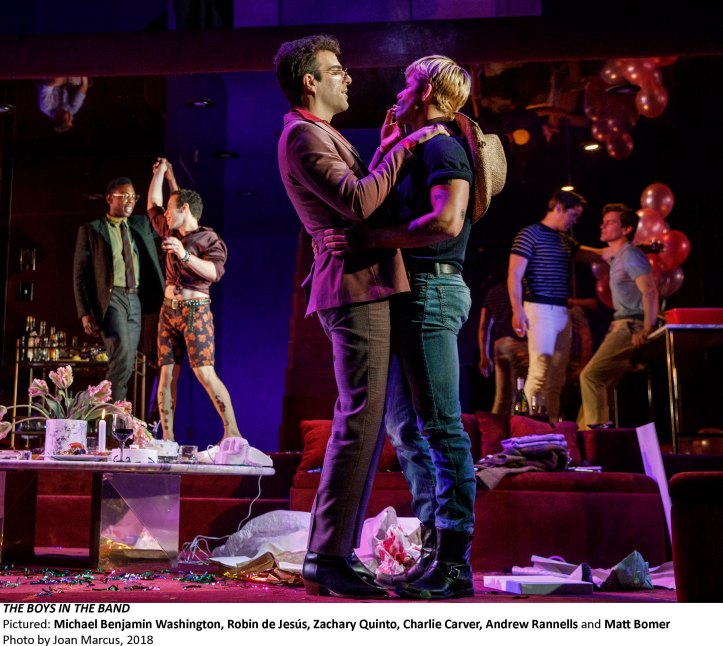

Each time the doorbell rings, Michael thinks it is this straight-laced man, but it is the party guests in a pack, minus the birthday boy. He comes later, fashionably late as predicted. Flamboyantly arriving at the party is Emory, played with a wild abandonment by the clear-minded Robin de Jesus (Broadway’s In the Heights, Rent), followed by the one black man at the party, Bernard, played strongly by Michael Benjamin Washington (Broadway’s Mamma Mia!, La Cage aux Folles), and the handsome but bitterly tense couple, Hank and Larry, played with a sexually controlled edge by the suited Tuc Watkins (Cherry Lane’s Fortune’s Fools) and the tightly clad sexual beast, Andrew Rannells (LCT’s Falsettos, The Book of Mormon). The gifts are piled in the corner, just as fast as the jabs and jokes start to fly at one another. They have all come together in lancing love to celebrate the birthday of Harold, played with a hard veneer by the dry Zachary Quinto (Off-Broadway’s Angels in America, Broadway’s The Glass Menagerie), but before he or the old college buddy arrives, one more gift comes hand-delivered in the form of the beautiful and deliciously divined Charlie Carver (HBO’s “The Leftovers“), giving us the best gay cowboy ride seen on Broadway. Their camaraderie is deliciously solid and specific, engagingly filled with a neediness for love and acceptance, maybe not emanating from within, but wanted from each other. They bicker and poke at each other, picking at their own scars, while inflicting more on each other, with love. It’s spectacular to watch these pros work their way around the room, all the while being personally relieved to be merely an observer rather than a guest.

Once that spotlight of vodka gets poured, this game of shredding each other begins with full brutal force. The main focus of Michael’s vicious anger comes from an idea he has about Alan, and one he is desperate to force out from his overwhelmed and drunk college friend. His current friends, caught in the cross fire, each step up and expose themselves in ways that even when the structure feels forced, it still resonates. It’s hard at points for this modern gay man to take the mean-spirited attacks on one another. It’s a stereotype that maybe modern gay culture would like to erase, but it’s still there, maybe not as blatant as it was, but that self-deprecating wit still survives lurking in the corner at every party. There is some strong authentic truth in the play, especially taken as a hard look back at where we came from and where we are trying to be now. Quinto’s laconic and droll delivery wears a bit, but its truth and power never dissipates, building to a complex battle between two men who love and need each other in ways that are too difficult to convey. His performance, along with Parson’s, details the tortured soul in a way that is both brutally funny and wickedly devastating. I have never seen the 1970 film, directed by William Friedkin, but I’m thankful to have had the chance to see this rendering. I hoped for a slight bit of redemption, but what I got was far more detailed and intense. Back in the day, Boys in the Band was called “A true theatrical game-changer” showcasing the result of being gay in a world that was not willing to accept them. It’s a testament to that time and a warning for us all, as we watch the powers that be right now attempt to push us back into that shame-filled closet demanding that we hide out scared in our pink apartments. I don’t want to reverse the progression. I will #resist.

[…] Globe’s Much Ado About Nothing), and strong sound design by Leon Rothenberg (Broadway’s The Boys in the Band). Gregory transforms himself, galloping this way and back through time and a wide age range with […]

LikeLike

[…] Brian MacDevitt (Broadway’s Carousel), and solid sound by Leon Rothenberg (Broadway’s The Boys in the Band), this beautifully edgy, slightly cool, book-educated family take on the task with a strong sense […]

LikeLike

[…] season’s production of The Boys in the Band was not eligible for Outer Critics Circle Awards because the production did not accommodate the […]

LikeLike

[…] directed with a sharp and piercing eye for conflict and clarity by Joe Mantello (Broadway’s The Boys in the Band, The Humans), the political chess game is a thrill and a hoot to witness. It’s a memory of […]

LikeLike

[…] The Boys in the Band by Mart Crowley […]

LikeLike

[…] are given, not Smith this time around , but Michael Benjamin Washington (Netflix/Broadway’s The Boys in the Band), taking over the performance reins, embodying each and every one of her creations with […]

LikeLike

[…] is not Smith this time around, but Michael Benjamin Washington (Netflix/Broadway’s The Boys in the Band), taking over the performance reins from the earth goddess, embodying each and every one of her […]

LikeLike

[…] its weight in donated gold. And then donate, for a second time, as Zachary Quinto (Broadway’s The Boys in the Band) asks again and again in the awe-inspiring “I Promise” written by Adam Bock (A Life) […]

LikeLike

[…] its weight in donated gold. And then donate, for a second time, as Zachary Quinto (Broadway’s The Boys in the Band) asks again and again in the awe-inspiring “I Promise” written by Adam Bock (A Life) […]

LikeLike

[…] Quinto, presentation by Playbill of Mart Crowley’s The Men From the Boys, the 2002 sequel to The Boys in the Band on June 26th (available here for streaming through June […]

LikeLike

[…] pretty beautifully by David Zinn (Broadway’s Boys in the Band), with sharp lighting by Kevin Adams (Broadway’s Cher Show), lovely costuming by Susan […]

LikeLike

[…] with an abundance of alcohol and accussations – much like the much stronger (although dated) Boys in the Band back in 1968 (and in the stellar revival in 2018), the end result that landed on the Tony Kiser […]

LikeLike

[…] a bit clumsily by David Zinn (Broadway’s Boys in the Band), with sharp and detailed lighting by Kevin Adams (Broadway’s Cher Show), overly fussy and loud […]

LikeLike

[…] by herself and her husband, Jim Baker, played with precision by Andrew Rannells (Broadway’s Boys in the Band). So much to pick your way through, and so little time (even though the show ran about 3hrs […]

LikeLike

[…] between the New Left liberal, Gore Vidal, played to perfection by Zachary Quinto (Broadway’s Boys in the Band), and the staunch conservative, William F Buckley Jr, played by the powerhouse David Harewood […]

LikeLike

[…] of Pi), lighting designers Tim Lutkin (Old Vic’s Lungs) and Hugh Vanstone (Broadway’s The Boys in the Band), video designer Finn Ross (Almeida’s Tammy Faye), sound designer Gareth Oen […]

LikeLike

[…] Josh Gad (Broadway’s Putnam County Spelling Bee) and Andrew Rannells (Broadway’s The Boys in the Band), live loud and funny on stage, hamming it up big time as buddy writers of a musical, then the […]

LikeLike