The Streaming Experience: Old Vic’s Mood Music

By Ross

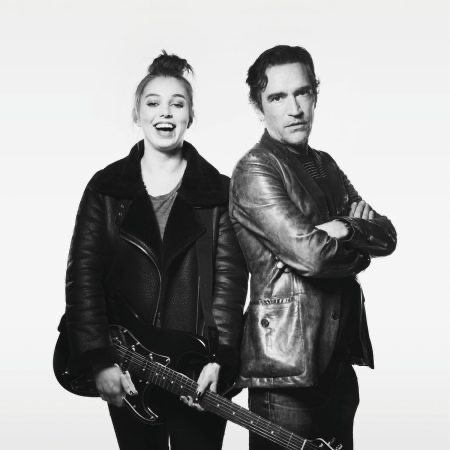

“Why are you here?“, she asks, and for a while, we wander around Old Vic‘s Mood Music in a similar confused but intrigued manner. Joe Penhall (Sunny Afternoon, Blue/Orange) has written a compelling piece of music industry introspection, that circles and circles around the subject like a boxer looking for the punch that will won him the belt. With a keen eye on unpacking what’s at the heart of this debate, that match bell rings signaling that the battle has begun. Starring the magnificently adept Ben Chaplin (Donmar’s This Is How It Goes) and the nuanced authentic Seána Kerslake (Lee Cronin’s ‘The Hole in the Ground’) as musical talents at odds over intellectual artistic property, the fascinating struggle stomps forward under the watchful eye of director Roger Michell (‘Notting Hill’, ‘Enduring Love’) in a strategic stance that doesn’t always completely hit its intended target, but the drive and beat of the musical boxing match never lets us completely jump off the topical metaphoric hook.

In the stronger Young Vic production of Penhall’s Blue/Orange, the moral crisis stomped forward similarly, with that battle raging between two white mental health doctor experts playing a winner’s game over a black mental patient’s care. That play asked us to untangle a batch of complex concepts, such as race, power, ethics, and ethnocentric preconceived notions of outside influences on other ethnicities that differ from the therapist’s. It was a mouthful when I saw the play in 2016, sounding like a topical thesis in the making, but the challenge was to take on the task of trying to figure out where we stand in this ever-changing construction and argument. The same could be said of Mood Music, although the topical instrument here is artistic control, particularly when gender and the power of the establishment, i.e. older white men, become players in the intense conflict over ownership of a song.

“Where would you like to start?“, she asks soon after the first question. And the combative circling begins with a vengeance with separate conversations mixed together interspersed with one another, something akin to a Sondheim song. Surprisingly, the Sondheim lyrics rings more true as the voices layer over top of one another telling numerous vantage point stories at the same time without the carefully timed awkward pauses. The dialogue scenarios switch exactingly between artists and their therapeutic counselors or, at other moments, their legal representatives. The construct drives the rhythm forward, although at times feels internally disjointed stalling the emotionality at the center of the conflict. It becomes structural rather than emotional, but the thrust of the stage, aggressively designed by Hildegard Bechtler (NT’s After the Dance), with lighting by Rick Fisher (West End/Broadway’s Billy Elliot) and costumes by Dinah Collin (‘My Cousin Rachel’), pushes the fight out into the audience like a boxing match, with lawyers coaching the artist fighters into a battle that might not have any clear and true winners, unless you only look at the battle through one specific lens.

Penhall layers the different tracks with a solid stroke of the pen, never letting up with the complexities of ownership and morality. It’s clearly a betrayal, with the artist-producer, Bernard, played exceedingly well by Chaplin, exploiting the naive young Dublin-born singer-songwriter, Cat, played to perfection by Kerslake. The extremely well-balanced fluidity of the six-person argument catapults the characters into souls greater than the idea put forth by Bernard. He states, most dishearteningly that actors are mere mouthpieces to be used, but the concept is fractured by Chaplin’s own deliciously detailed performance of the despicable, but ever so sad, music producer. It’s so easy to dismiss the unloveable man, but the delicate dance of making him real and nuanced does the job. It isn’t an easy one, but Chaplin makes it clear he knows how to play those notes so very well. Kerslake sings a similar tune, and even though her character is infinitely more likable from moment one, the complexities of her dilemma with her father resonate wisely and deeply, hitting the target with a fighter’s force. She brings energy and anger to the exploited Cat, and although Penhall does formulate within some blurry lines in regards to the idea of solo authorship of a piece of music, the battle for integrity tends to bypass the manipulative old white man to find its mark sitting comfortably in the heart of the exploited young artist. Gender and age/stature is aggressively entwined in the arguments, laid out precisely by the players in a particularly shocking manner, especially when Bernard claims sole credit for the hit single they created together in the studio based on one of Cat’s songs. The conflict flies up into the complex heavens as both parties enlist lawyers to intensify the battle, and seek psychotherapists to help them sort out the complexities of betrayal and despair. It’s a fascinating mix, law and psychology in each of the corners, trying to support their fighter with all the help they can give.

But do they enlist these helpers with the same focused determination? Not so much, as Bernard’s persona is that of a self-centered bully with complete contempt for not only the musicians and artist/singers he works with, but therapy itself. He seems to look to his therapist, Ramsey, played well by Pip Carter (NT’s The Seagull) as more of a reflective sounding board to hear himself speak. Being a therapist myself, he’s the type of patient who only seeks validation for his brand of action, rather than really wanting to investigate his inner drive and function. Whereas Cat engages with her therapist, Vanessa, concisely portrayed by Jemma Redgrave (Hamptstead’s Farewell to the Theatre) in a more introspective manner, trying to understand her inexperienced self and the vulnerability in her stance. Both therapists are given slightly bent dialogue to deliver and lead, not only their patients but the play forward into conflict. It doesn’t always ring psych therapeutically true and authentic, but the defense does drive the formula into conflict with confidence. The dynamics and detailed arguments challenge the status quo while ‘rock and rolling’ the battle around the ring impressively. The idea that the music industry treats its female artists poorly never gets much inner movement or deeper deconstruction, although it is clearly stated and proven without a doubt, but we sort of knew that from when it “all started in rehearsal.” There’s no development in that war, sadly, and we all have to sit uncomfortably watching Bernard sideline Cat in the catastrophic acceptance speech when most of us want her to push back hard and find the way to see through the fog of his manipulations.

Dramatically, it’s clear whose side we are on, I’m hoping. Penhall does a pretty great job giving complexity to the give-and-take of musical artistry, but greed and power dynamics tend to outweigh those intricacies on the moral scale. Cat represents every artist who has ever lost the battle against the powerful music industry, with her gender and her age weighing heavily against her. The contemptible Bernard equates female singers as voices who “breathe life into words they didn’t necessarily write,” while maintaining that it is in his eyes and ear where the true creative force lives. But we know that is not true, almost from the moment he opens his mouth. Everything is thrown about by lawyers, well played by Neil Stuke (BBC’s “Silk“) and Kurt Egyiawan (‘Beasts of No Nation‘), and structurally underwritten therapists who try to solve and win battles, while somehow not really seeing what is at stake. The play fluctuates between completely engrossing to repetitious and distancing. We don’t hear enough from the artists within, doing the thing that they are talking about, but the unresolvable issues resonate from a truly authentic spirit. The inner music drives forward as only well-crafted beats can, with mystery and power. There’s difficulty in controlling our emotional sense when listening and diving into to music and creativity. And in Mood Music, we feel and inhabit that art, and give in to that pulse and structure, with pleasure and a captivating presence.

[…] even as the tables are turned on that dynamic set designed by Hildegard Bechtler (Old Vic’s Mood Music), who also did the costuming. It gives a solid access to see and take in every argument from every […]

LikeLike

[…] the tables are turned on that dynamic set designed strongly by Hildegard Bechtler (Old Vic’s Mood Music), who also did the detailed costuming. It gives solid access to see and take in every argument from […]

LikeLike