The London Theatre Review: National Theatre’s The Father and the Assassin

By Ross

Weaving together a memory play with a psychological study of epic historical proportions, the National Theatre delivers a mystery revolving most dynamically around a murder up close and personal. Three bullets fired, we are told by our engaging narrator, Godse, portrayed most cleverly by Hiran Abeysekera (RSC’s Hamlet), all by him, but he says it almost triumphantly. “Even you could turn into me,” he also explains, and in that moment I realized that I knew so little about that sad chapter in India’s political history. Other than the headlines, I might add, but more so that there had to be another side to the assassination story of one of the greatest and most well-known Indians who ever lived, Mahatma Gandhi, and I couldn’t stop myself from leaning in to see and understand just what playwright Anupama Chandrasekhar (When The Crows Visit; The Snow Queen) has in store for us.

“Let’s not exaggerate,” but those three bullets changed history and shocked the whole world, mainly because of the confusion it elicited. Set against the backdrop of the tumultuous conflict between India and its colonizing oppressors, the British Empire, The Father and the Assassin attempts to both outline the political journey towards Indian independence and give us a closer more intimate look at the man who fired those shots. Chandrasekhar has noted that thousands of books have been written about Gandhi in an attempt to understand and know every aspect of this famed philosopher and political public speaker and writer, yet very little about his assassin, particularly his upbringing and what would bring a man like him to this violent moment. This was the play’s intent.

“Any dramatization of history requires a degree of imaginative license,” she tells us in her notes, and here on the grand Olivier Stage of the National Theatre, this epic tale revolves forward revealing an upbringing of disorder and subtle discourse. To understand, or at least attempt to understand the central figure and our narrator, we have to peer back into Godse’s upbringing when his parents, and try to look beyond the act itself. You see, after losing three other boys in their infancy, Godse’s parents sought a somewhat odd religious solution to their situation and his birth. They decided, in order to sidestep what they thought was a curse on their family, to raise their boy as a girl. They would pierce his nose and deliver him into the world as a daughter, forever setting up a conflict that may have caused Godse to be quite lost in his own personal identity, possibly making him far more susceptible to father figures who might give him a structural meaning of self and acceptance.

This is Godse’s conflict story, of inner and outer divisions and betrayal of the father, played out in identity politics of a different order, resulting in some trauma and childish animosities that have their roots in personal relationships as well as, metaphorically speaking, political colonialism. At least, this is what Chandrasekhar tries to deliver forth in this psychological study alongside a complex paradigm for Hindu nationalism, all located in the central figure’s cracked psyche, which, in essence, may have resulted in the 1948 assassination of Gandhi.

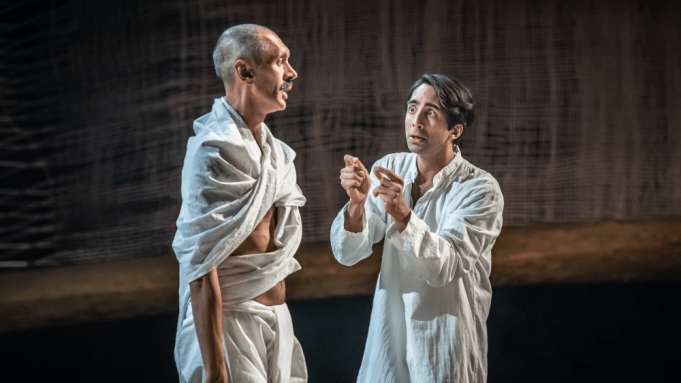

It’s an exhilarating explorative adventure, laid out majestically (and somewhat typically) on a set on that grand Olivier stage. Rust-colored and ramped in the round, designed well by set and costume designer Rajha Shakiry (NT’s Trouble In Mind) with grand lighting by Oliver Fenwick (Audible’s Girls and Boys) and a solid sound design by Alexander Caplen (Royal Court’s Over There), The Father and the Assassin unpacks the complicated quest of a young boy to find purpose and an identity that would bring him, first to Gandhi (Paul Bazely) and his unifying movement of peaceful resistance. This dynamic laid out a fatherly framework that would be their undoing, as that relationship was followed by the divisive politics of Vinayak Savarkar (Tony Jayawardena), who built the foundations of the Hindu Mahasabha party pushing a strongly formatted idea of Hindu nationalism as a political ideology, all while serving out a life sentence in the Cellular Jail as a prisoner. It was a switch that changed the world, but one that seems to have been drawn from paternal inclinations and rejection, rather than political identifications.

The large cast of twenty does the piece grand service, as we play along with Godse as he, as a child, supports his family by channeling the goddess as a village fortune teller. It’s a captivating first engagement, as it weaves and rotates into view a childhood filled with obedience, and respect, followed directly by rebellion and political and personal debate.

“Hope smells a lot like sandalwood,” we are told, and the play unfolds with precise non-linear structuring that digs us deeper inside this fractured mindset. As directed with clarity and vision by Indhu Rubasingham (59E59/Round House’s Handbagged), the story sings on a whole other range, playing with our sensibilities and understanding of an event that shook the foundations of our world. With a staging that conjures up multitudes of complex psychological images, as well as dialectic themes of political style and belief structures, Godse becomes something of a childlike shell, trying desperately to control his narrative while batting away childhood trauma, embodied well, in contrast, with the peaceful qualities of his open-hearted childhood friend Vimala (Dinita Gohil) and the games they once played.

The play lives and breathes through the essential performance of Abeysekera as Nathuram Godse. The way he moves about is both delicate and angry; aggressive and casual, allowing playfulness to be weaved within the construct of empowerment and weakness of character. His desperation for fatherly and an authentic understanding of his own identity is at the center of this dynamic new play. His put-upon strut of childish resentment and ultimate vindictiveness delivers in the end, with the pulling of the trigger. The Father and the Assassin ends on a note of complications, energizing the room to seek for more clarity and understanding. It’s a complicated ending, leaving you questioning its stance, and making us want to know more. Which I think is precisely the point.

[…] “The Father and the Assassin” Enlightens and Questions at the National Theatre, London […]

LikeLike

[…] his dutifully assistant Carmen Ghia, portrayed glittery and gloriously by Raj Ghatak (NT’s The Father and the Assassin), the framing is reformed as perfect as one could ever hope for, and delivered in near perfect […]

LikeLike