A Frontmezzjunkies Film Review: The History of Sound

By Ross

“My father said it was a gift from God. How I could see music. I thought everyone could see sound.” These are the first lines spoken, from a man looking back, and trying to understand a life lived and loved. Those words, spoken with a clarity that is drenched in grief and pain by Chris Cooper (“Adaptation“), draw us into The History of Sound and take us by the hand, gently, to lead us down through the woods. Some films move through you softly, like a song you only notice once it’s gone. Then there are films like this one, vibrating somewhere deeper, ever so quietly, insistent, until you realize you’ve been carrying their echo long after the final frame has gone dark.

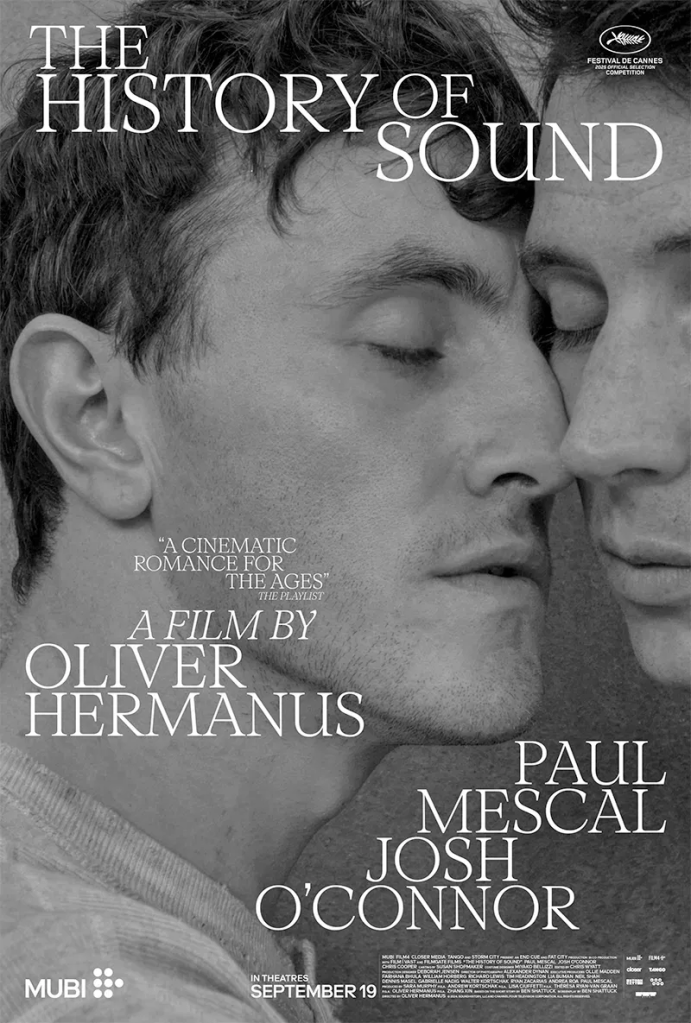

Director Oliver Hermanus (“Living“) unfolds this tale like a memory rediscovered. It is fragile, luminous, and it quietly trembles at the edges. Set in 1917, the film moves to the vibrations of a folk song, deep and spiritual, as it follows two young men, Lionel and David, portrayed by Paul Mescal (“Hamnet“; A Streetcar Named Desire at BAM) and Josh O’Connor (“God’s Own Country“; NT’s Romeo and Juliet), who meet at the Boston Conservatory, discovering in one another a shared devotion to the folk songs that pulse through the landscape of a divided, newly modernizing America. Their connection begins with music, but its frequency deepens almost immediately, humming with a sense of inevitability.

When David returns from the war, still searching for steadiness in a world reshaped by violence, he invites Lionel to join him on a “song-collecting” journey through the backwoods of Maine. Their task is deceptively simple: knock on doors, sit at rural kitchen tables, and travel the American countryside, gathering folk songs and capturing them on wax cylinders. They are the voices and melodies of a country still learning how to hear itself, but they are only the backdrop; the true music of the film is the way these men look at one another, the way they lean into silence together, as if trying to decipher the sound of their own hearts. And in their wandering, the journey becomes something far more intimate, a quiet love story that blooms with a casualness achingly rare for its time. Their affection deepens mile by mile, taking shape in the quiet darkness between towns and in the songs that shadow their long walks. It feels as natural as breathing.

Mescal has a gaze that feels almost sacred here. His eyes carry a gentle story, admiring, seeing David with a fullness that borders on devotion. O’Connor meets that gaze with a kind of trembling yet carefully composed restraint, a soul wrestling with both desire and the quiet weight of inherited shame. Together, they create a portrait of connection so tender it almost feels like trespassing to witness.

Hermanus and cinematographer Alexander Dynan (“Goodnight Mommy“) give them a world worthy of that tenderness. Muddy roads drenched in shadow, Rome washed in blinding white, an English countryside soft enough to bruise, each landscape seems to hold their longing like a cathedral holds light. Even the air around them seems attuned to what they cannot say.

Yet some of the film’s most piercing moments belong to Molly Price (“Babygirl“) as Lionel’s mother, whose presence haunts the story with the force of a cherished folk song. In a memory sequence, her laughter feels ancient and earthbound, bubbling up like something too dear to fade. But when illness wears down her voice, she becomes somewhat intertwined with the sadness settling inside Lionel. And it both binds him and holds him down from a journey he just has to eventually take.

But stories shaped by music are rarely free of dissonance. Life, as always, intervenes. After their journey ends, Lionel returns to school in England; David stays behind. Letters are written into the void. Seasons pass in silence. A bright, spirited fellow student, beautifully embodied by Emma Canning (“Say Nothing“), enters Lionel’s orbit, urging him toward a future he tries earnestly to believe in. But when he is called home to Kentucky as his mother grows ill, the music he thought he’d lost begins to circle back toward him, carrying truths he is not quite prepared to face. (And there’s a lovely cameo by my friend, the wonderful Dawn McGee that made me smile. Congrats!)

Ben Shattuck (“Sweet Freedom“) etches something haunting in his script. Adapted from his own short story, he treats language as both burden and gift. It knows that some truths can be held in the air like a song but never spoken. That silence can be its own kind of confession. That longing often sounds like breath held just a moment too long. It’s a script that trusts us to listen with intention and patience, for the catch in a voice, for the rustle of a feather falling from a pillow, and for the emotion that flickers across a face before retreating back into the dark.

“Write. Send chocolate. Don’t die.” And then there is that moment in the train station, one of the most devastating and quiet scenes in recent queer cinema. Two men who have shared everything except the words they most need. A goodbye swollen with all the things that cannot be said aloud. A love suspended, like a note left unresolved, and a fear that these two may never see each other again.

The film is also, quite simply, a musical wonder. Mescal and O’Connor both sing with an unaffected, lived-in quality that makes the folk songs feel like private offerings—pieces of inherited emotion passed hand to hand. Sam Amidon’s arrangements turn these old tunes into something vast and immediate: hymns about murder, morality, devotion, and everyday longing. Their collective force sweeps you into a world shaped by roads not taken, songs almost lost, and love felt in vibrations rather than declarations.

To watch The History of Sound is to be reminded that some connections exist outside the words we’ve been given or allowed to say. That desire can be as gentle as a brush of fingers, as devastating as withheld speech. That love, when treated with this kind of care, can feel like a living thing, most delicate, radiant, and impossibly human.

This is not merely a film. It’s an ache and a hymn. A quiet miracle of seeing and being seen, even if the words remain quiet or unspoken. And when it ends, you don’t walk away from it so much as you continue carrying it, like a suitcase filled with musical memories, as though some small part of its sound has lodged itself inside you, still vibrating. Still listening. Still alive.

[…] beyond May, my name already sits nervously on waitlists for the future. Josh O’Connor (“The History of Sound“) in Golden Boy at the Almeida feels like a collision of star power and political rage that […]

LikeLike