The TIFF Film Review: Alex Winter’s “Adulthood” & Andy Hines‘s “Little Lorraine“

By Ross

Two solid commercial films were presented at the Toronto International Film Festival; one at a big, starry Gala Presentation at the Roy Thomson Hall, Toronto, and the other, a smaller Canadian film, was screened more quietly at the TIFF Lighthouse. Both fulfilled their agreement with the audience to entertain and engage, but it was the smaller film, “Little Lorraine“, that ultimately landed the deeper emotional punch. That film’s storytelling was framed with more conviction and heart than the larger-budgeted “Adulthood“, which is a whole lot of fun, but struggled with an overall sense of emotional logic and connection.

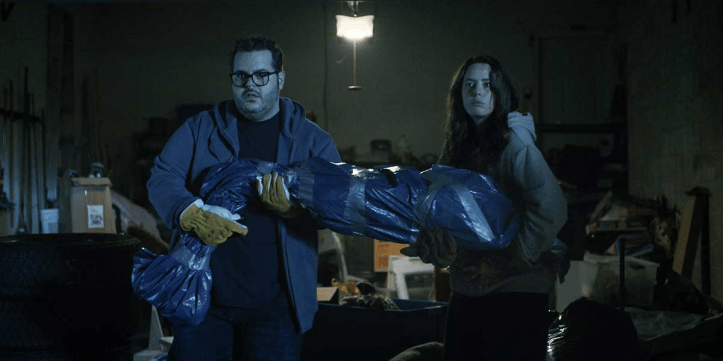

In “Adulthood“, Alex Winter (yes, the one-half of Bill & Ted; Broadway’s Waiting for Godot) trades in his documentary directorial instincts for something more narrative and completely mischievous. Inside this devilishly comic neo-noir, the film shuffles out a “where would you hide a body?” kind of energy, hovering between dark satire and family farce. Kaya Scodelario (“The King’s Daughter“) and Josh Gad (“Ghostbusters: Afterlife“), as estranged siblings Meg and Noah, spark a lively familial chemistry that carries the film’s hidden-behind-walls absurdist premise. Two adults cleaning out their family home discover a literal skeleton in the basement, and the discovery sets off a chain reaction of cover-ups, bloodshed, and bizarre encounters with a resentful home-care nurse (Billie Lourd), a sword-wielding cousin (Anthony Carrigan), and an inquisitive detective (Camille Games).

Winter (“Zappa“) directs with comic flair and a strong sense of genre play, leaning into visual gags and hilariously timed reversals. Written by Michael M.B. Galvin, it’s a polished, tightly edited ride, smartly paced, consistently entertaining, and confident in its tone. Yet, somewhere within all the sharply crafted chaos, the film loses its connective touch with its true emotional stakes. The irony eventually overwhelms our empathy. Not surprisingly, Gad’s performance is overtly loud and nervy; Scodelario, meanwhile, finds the film’s rare, more carefully constructed tones, grounding moments of panic in something that resembles real pain. Still, by the time the blood begins to splatter across the bridge and the plot loops back on itself, we’re laughing, but not exactly from a caring perspective.

That’s where “Little Lorraine” ultimately surprises. Writer Andy Hines’s smart directorial debut takes a familiar “based on a true story” setup, working-class men pulled into organized crime, and breathes new life into “uncertain futures” with moral gravity and a sharply defined emotional core. Set in 1986 Cape Breton, it begins in a claustrophobic fireball of tragedy: a mining explosion that kills ten men. The nightmarish event leaves an entire community adrift, traumatized, and desperate. From there, the story turns towards the ominous sea, as the fatherly, out-of-work miner Jimmy, portrayed deeply by the appealing Stephen Amell (“Arrow“), and his two best buddies, reluctantly join his great uncle Huey, played magnetically by Stephen McHattie (“Watchmen“), aboard a lobster boat. On shaky sealegs, the three aren’t comfortable with the plan, but with families to feed, they set out anyway, only to discover that the boat’s lobster cages mask something far darker: an international cocaine ring, floating and smuggling their illegal goods into Canada.

Where “Adulthood” feels like a darkly clever game of hide and seek, “Little Lorraine” feels more like a wild and windy rainstorm that blows in from behind. Hines’s quietly smart direction captures the salt, sweat, and financial seduction of the work onboard the boat with striking intimacy, floating forth the lapping rhythm of the tide, the briny smell of lobster, and the claustrophobic angst of moral compromise. The film’s dynamic visual texture is extraordinary for a debut, with cinematographer Jeff Powers (“Reverse the Curse“) rendering the Cape Breton coast as both a paradise and a place of paralysis, where loyalty and desperation mingle in the sea air. Hines, best known for his Grammy-nominated music videos, brings that same visual rhythm to narrative form, but tempers it with patience, purpose, and tense power plays.

The performances are uniformly strong, with Matt Walsh, Rhys Darby, and Sean Astin adding solid structure to this vessel, but it’s McHattie’s presence that gives “Little Lorraine” its captivating, bruised soul. His Uncle Huey is both a familial mentor and moral menace, a ghost of an older, rougher Cape Breton. Amell, known mostly for action roles, delivers his most grounded work yet, capturing the moral panic of a man who wants to provide but can’t stomach what he has become. Auden Thornton (“Beauty Mark“) almost steals the film away from the men, as Emma, Jimmy’s wife, while Colombian reggaeton singer, J Balvin, in his first acting role as an Interpol agent, adds a strange, feisty flair to the proceedings, especially with his uniquely out-of-place dressed frame, costumed by Olivia Hines (“Escape the Night“), adding a burst of global energy to an otherwise very local story.

If “Adulthood” is about burying the past, “Little Lorraine” is about being buried by it. Both films hinge on the weight of family and secrecy, but Hines’s film resonates because it takes its time to listen to what those secrets mean. Its tension feels earned, not manufactured; its characters haunted by recognizably human choices. The final act doesn’t explode so much as it deepens, rippling outward and downward with moral consequence.

What’s striking, seeing the two films so close together, is how they mirror the cultural divide between Hollywood irony and Canadian sincerity. “Adulthood” is slick, self-aware, and clever in its detachment. It wants us to laugh at the absurdity of guilt and self-absorption, while “Little Lorraine” wants us to feel the weight of their adulthood pulling them, and us, down into the depths of the Atlantic. Its drama is rooted in community, consequence, and chaotic moral combustion. One treats crime as a hilarious metaphor; the other as a complicated moral inheritance. Both are valid, but only one stays attached to our soul like a fishhook.

And that, perhaps, is what TIFF does best, placing films of wildly different scales and ambitions side by side, allowing us to trace the spectrum of storytelling itself. In one screening, the joy of genre; in another, the ache of authenticity. Watching “Adulthood” and “Little Lorraine” basically back to back reminded me that cinema, at its best, still offers both: the glittering spectacle and the grounded truth, the world we escape to and the one we can’t quite leave behind.