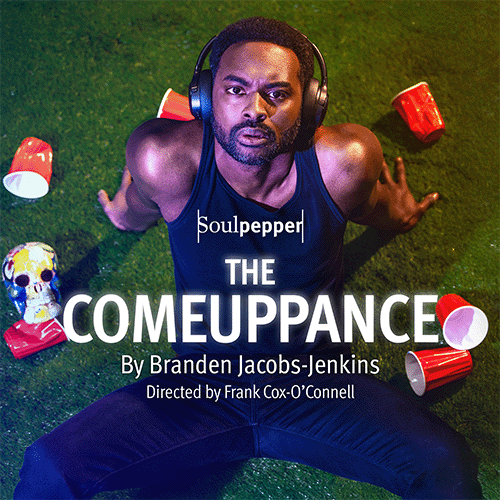

The Toronto Theatre Review: Soulpepper’s The Comeuppance and Icarus Theatre’s DNA

By Ross

Death has been lurking on the edges of Toronto’s stages lately, threatening and messing with the lives of those who stand before it. It is a determined presence that watches, curious and controlling from the sidelines, and forever fascinated by human frailty, regret, guilt, and the uneasy compromises we make to survive. And the lies we fabricate. In Branden Jacobs-Jenkins’ The Comeuppance at Soulpepper Theatre and Icarus Theatre’s DNA at The Theatre Centre, death is not a single stance but an atmosphere, and energy. In one, it stands before us in glowing white, proclaiming its curiosity and its sharp, mysterious intent, but in the other, it hangs on the edges in the air, corrupting connections and breaking them down like fall leaves. It seeps through the cracks of ordinary conversation, like the weight of silence and regret, carrying with it the flicker of guilt and corruption in a shared glance or action. Each play, in its own way, asks what happens when we turn away from what’s right and what remains after the wrong has been unleashed or buried. And both captivate and contain all that is lost and found inside our found familial bonds when Death comes a-calling.

The shocking white face of death, literally, waits in the doorway before the show even begins, its shadowy presence framed by a dim porch light and a swing that creaks like an omen. It’s a chilling and inspired start to Soulpepper’s The Comeuppance, the hauntingly surreal play by Branden Jacobs-Jenkins (Purpose) about old friends, unfinished business, and the inevitability of reckoning. Directed by Frank Cox-O’Connell, this Canadian premiere takes the playwright’s sharp social wit and turns it toward something quieter, more insidious, serving up the question of who we’ve become in the aftermath of loss and isolation, and whether our shared history, watching us like ghosts, is any more forgiving than the ones we carry within.

The figure has much to tell us before this group of former high school classmates, once self-described as a gang called the “Multi-Ethnic Reject Group,” gathers together on a porch to “pre-game” before their twentieth reunion. The evening begins in casual laughter and nostalgia, but the energy feels tight and combustible. There is historic affection, especially for the host of the event, but that sense of unease remains, building as alcohol, marijuana, and old history dissolve the fragile boundaries between affection and resentment. Death itself dances from within as a kind of narrator, drawn to the contradictions and the thin line between personal performance and confession. Cox-O’Connell stages this haunting with precision, allowing Jacobs-Jenkins’ layered writing to unfold in gestures and silences as much as in words.

The ensemble work in The Comeuppance is superb. Ghazal Azarbad (Soulpepper’s The Welkin) as Ursula gives a performance of clear, soft intelligence and aching self-awareness, while Mazin Elsadig’s Emilio conveys the quiet, imploding grief of a man who cannot quite forgive himself. Carlos Gonzalez-Vio’s Francisco balances spicy empathy with exhaustion, Nicole Power’s Caitlin hides her unease behind composure, and Bahia Watson’s Kristina crackles with defensive wit and chaotic vulnerability. Together, they form a delicate constellation of shared history and mutual disappointment. At times, the emotional escalation feels hurried, the eruption of anger arriving before the deeper intimacy has had a chance to breathe, yet the performances remain gripping and engaging. Each actor finds in their troubled character a recognizable fragility, the sense that they are still living in the long shadow of what they once were to each other and to themselves.

Visually and aurally, The Comeuppance is unified. The porch set, designed by Shannon Lea Doyle (Soulpepper’s The Seagull), feels both familiar and slightly otherworldly, its wood and shadows holding the residue of memory. The costumes, designed by Ming Wong (SP/TMSC/Crow’s Octet), trace the faint absurdities of middle age, while Jason Hand’s lighting hypnotically shifts from warm dusk to spectral glow in an instant. Olivia Wheeler’s sound design deepens the unease, echoing scene transitions into an otherworldly pulse. Together, the design team grounds the play’s metaphysical reach in sensory detail, allowing us to feel death’s curiosity as both threatening and strangely tender.

If The Comeuppance exposes the fault lines of adulthood, Icarus Theatre‘s DNA, magnificently directed by Erik Richards (Coal Mine’s Dion), investigates the origins of that fusion and fracture. The stark and unsettling play, written explosively by Dennis Kelly (Girls and Boys), traps ten teenagers in the aftermath of a terrible accident. A prank gone terribly wrong during a wild night of hilltop partying leads to the apparent death of a classmate, and the group, in their panic, chooses concealment over truth. They think first of personal survival, not of conscience. What follows is a portrait of moral disintegration; young people discovering the seduction of denial and the corrosion of consequence. Richards directs with a tight clarity, letting Kelly’s writing carry its own quiet menace up the hill and into the night air. The production’s sense of pace is remarkably taut and unrelenting, yet there is a solid attention to the small, human hesitations and personal needs and fears that make the story whole.

The ensemble of DNA performs with striking precision and commitment. The shifting mix of silence and endless chatter between Leah (Morgan Roy) and Ray (Chantal Grace) captures their power dynamic superbly, exposing the insecurity of youth and the authority of a non-committal shrug. Grace and Roy deliver a masterclass on unfair union, that echoes through the piece in such a way that when it returns, embodied by another (Ivan Anand), the effect is harrowing, striking, and real. And what first feels like bullying leadership emanating from the demanding John (a strong Jonah Fleming) literally vanishes under the pressure of guilt and shame, never to be seen again. His retreat feels symbolic of what guilt can do to an attempt to control, when the idea of threats and manipulation is replaced by others, like the psychotic Cathy, carefully delivered forth by the always impressive Emily Anne Corcoran (Icarus’s Constellations). Yet, each actor in this young cast, which also includes Seydina Soumah, Avril Brigden, Brennan Bielefeld, Haneen Paima, Zaniq King, and Jeremy Foot, expertly and fascinatingly locates a distinct drunken dance rhythm of guilt and self-preservation, shifting between bravado and silence as the truth begins to corrode their collective conscience.

The production’s minimalism heightens its tension. Nic Vincent’s lighting cut sharply through the darkness, evoking both the night of the incident and the lingering, unseen presence that haunts them days and weeks after the event. Some elements that seem of interest, like the plastic container containing Leah’s dead pet (costumes/props by Corcoran), or the hyper-brutalism of John, dead end in the woods, tucked away, never really finding their purpose. But up above, the cumulative effect of their desperately tight, gang-like union is devastating in its simplicity, reminding us of a teenage “Lord of the Flies“, but up on a hill near a school, rather than a remote island in the ocean. Death, here, is never personified, never announced, yet it fills the air with its profound consistency, revealing an invisible, yet devastating consequence that reshapes each of those who were complicit.

In DNA, death remains silent, unspoken; in The Comeuppance, it refuses to stay silent. One observes from the shadows, leaving its mark without a word. The other intrudes, speaks, and bides its time. Together, the two plays form a compelling conversation about accountability, friendship, and the slow, inevitable encroachment of mortality and connection. Both suggest that death is not an ending but a commenting magic mirror, reflecting who we were, what we’ve done, and how we try to live with our own choices: to have and to hold from this day forward, for better, for worse, for richer, for poorer, in sickness and in health, to love and to cherish, till death us do part.

Seen together, they reveal a continuum: from the reckless evasions of youth to the haunted reckonings of middle age. The teenagers of DNA might well grow up into the passive-aggressive adults of The Comeuppance, each carrying the residue of teenage decisions through a lifetime of silence and regret. Like marriage, one might say. And somewhere, just out of sight, Death still waits, patiently, compassionately, curiously, for that moment it will reach out and touch our hand.

[…] that the script does not. The spare geometric set, designed by Shannon Lea Doyle (Soulpepper’s The Comeuppance), creates space for imagination to wash in (although sometimes a bit too clumsily), while the […]

LikeLike