The Toronto Theatre Review: Public Consumption at Factory Theatre

By Ross

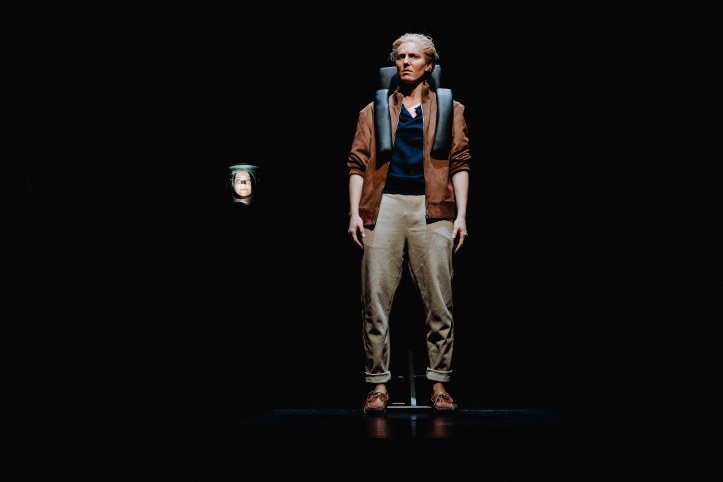

A lone figure stands sealed inside a bright, sharp square of light, their rhythmic, sensual movements unfolding like the first notes of an impending collapse. Framed like a specimen under tight examination, the initial engagement is unsettling, giving us access while keeping a sense of removal, or enclosure firmly in place. The sentencing comes soon after, and as Factory Theatre’s Public Consumption revs its deliberate engines, the hold it exerts becomes hypnotically powerful. Created by Lester Trips (Theatre) with Lauren Gillis and Alaine Hutton (Factory’s Honey I’m Home) as the play’s writers, performers, directors, producers, and designers, this content-warning-laden piece is exactly the kind of theatrical experience that makes you brace yourself before you even know why. It’s compulsively addictive and meticulously constructed: smartly conceived, tonally precise, and performed with an unnerving control that leaves you feeling speechless, but with a lot to say.

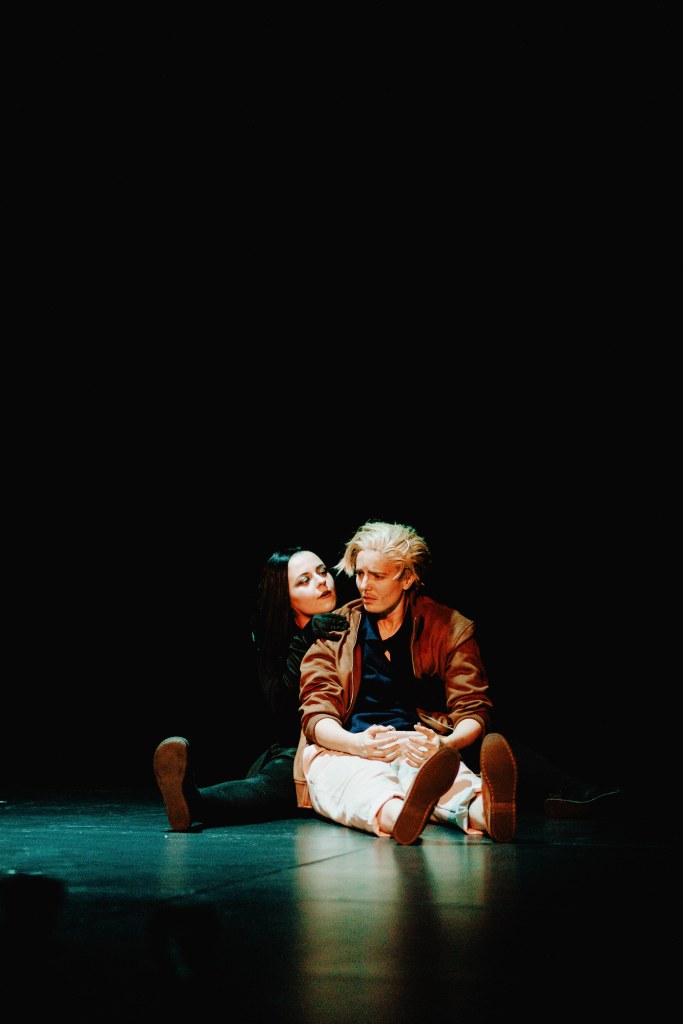

Yet its greatest impact comes from the complex and scratchy atmosphere it generates. Over 70 relentless minutes, the play burrows into the horrifying banality of moderating digital obscenity, not by showing the worst of humanity, but by placing us inside the body of someone forced to witness it. It’s almost impossible to describe the effect it has, but I felt my shoulders tighten almost immediately, as if preparing for impact, even when the production avoided the explicit imagery I feared it might unleash.

The play shares an odd, spiritual kinship with Max Wolf Friedlich’s JOB. Both explore the unseen labour of content moderation and the psychic corrosion it inflicts on the soul. Where JOB tells the story from the worker’s compulsive perspective and need, Public Consumption gives us a deranged, prison-cell-peephole view inside, imagining a role forced upon someone who once wielded celebrity power with impunity. Instead of an employee desperate to get back to her ‘meaningful‘ job, this construction gives us a fallen celebrity whose crimes, from sexual assault to cannibalistic text messages, echo loudly through the room without ever needing to be spelled out in their entirety. His self-pitying refrain, “Don’t they know who I am?” is at once pathetic, darkly funny, and chillingly familiar. It makes us laugh at his haughty bewilderment. And it clarifies, unmistakably, that his sentence of a mere 100 days’ house arrest feels absurdly light for the crimes implied, though to him, those days feel like an existential threat. In that framing, the play expertly draws its moral line.

The production’s sharp and brutal aesthetic is striking in its precision. The projections, designed by Denyse Karn (Studio 180’s A Public Display of Affection), with a strong helping hand by lighting designer André Du Toit (Factory’s Here Lies Henry), create a multimedia distortion field that mirrors his disorientation, especially when the lawyer looms large (and too close) over the stage like a glitching legal deity. Then there is the floating head of Duckie, an AI assistant tasked with guiding him through his new role. That visual, magnificently concocted, demands a cold, “Clockwork Orange” logic that becomes more disturbingly sinister with each task. The whole design team, including sound designer S. Quinn Hoodless (Factory’s Honey I’m Home) of Public Consumption, works in wicked astute synergy, where every rewiring effect and every sudden illumination feels clean, sharp, and surgically placed to jolt the audience without resorting to cheap shocks.

What the character endures is revolting, but the play smartly avoids lingering on the explicit content. Instead, it presents the job of content moderation as an assault on the senses, with “poorly written fanfiction porn” giving way to paid fantasy commissions, each more psychologically degrading than the last. It’s all conveyed with theatrical suggestion rather than spectacle, letting the actor’s spiralling performance and the audience’s own imagination fill in the darkest corners and the narrative fissures they produce. If there’s a structural weakness, it lies in those odd filmed commissions used as chapter markers. Each of them is visually playful but thematically incoherent as they never quite integrate into the otherwise razor-sharp architecture of the piece. They left me more puzzled than informed, even in the most subtle of ways.

Still, the cumulative effect is startling. Paired with a soundtrack that unexpectedly includes the disco-lilt of “How Do You Like Your Love?”, Public Consumption becomes a meditation on obscenity not just as content, but as a condition of modern life, in what we consume, what we produce, and what we ask others to endure on our behalf. It doesn’t exactly offer clarity, and the final product may feel murkier than the premise promises, but the experience itself is complex and gripping in ways that reverberate. It leaves you uneasy, alert, and disquietingly aware of the moral sludge running beneath our curated digital surfaces.

Public Consumption is ultimately profound and disturbing without being sensational; incisive without moralizing. It’s a deeply compelling piece of confounding theatre, a tight, disciplined descent into the ethics of surveillance, punishment, and the grotesque corners of the internet. It may not devastate as fully as one anticipates, but it lingers, prickling under the skin long after the lights come up and our phones are turned back on.