The Off-Broadway Theatre Review: This World of Tomorrow

by Ross

Quietly charming and deeply nostalgic, This World of Tomorrow, a new play written by and starring Tom Hanks alongside writer James Glossman, is premiering in high gloss at The Shed. It delivers a warm slice of nostalgia pie that is easily taken in and digested with a strong cup of coffee and a just a dash of cow’s milk. ‘Yes, really,’ says the past to the future, and directed with careful restraint by Kenny Leon (Broadway’s Our Town), this theatrical unwrapping feels like a pleasant time-bending romantic fable filtered through the DNA of movie-star Hanks’s own filmography. At its heart, it is a gentle, old-fashioned love story, less about paradoxes and plot mechanics than about longing, regret, and the human impulse to reach backward in time to correct emotional missteps. If the play occasionally moves at a leisurely pace, it does so intentionally, asking us to settle in rather than lean forward.

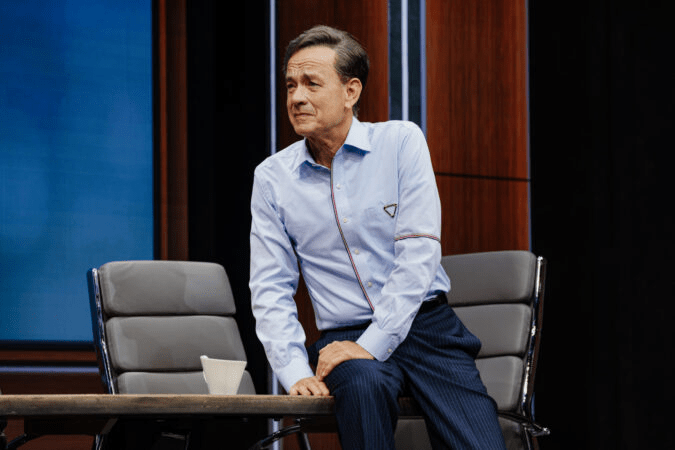

And that speed works, for the most part, even when it tests our patience and our attention. Mainly set across two timelines: 1939 and 2089, with one quick rainy detour to a Greek diner in the late 1950s, the play’s central conceit follows Bert Allenberry, played exactly how you’d expect from Hanks (“You’ve Got Mail“), a disenchanted wealthy scientist from the future who repeatedly returns to one perfect day at the New York World’s Fair in Queens. The device is clever and emotionally legible, though the depiction of the future itself feels oddly pared down and unimpressively flat. The high-concept elements, all those statistics, phone calls, and the presentation of ELMA, the External Learning Machine Associate, are addressed with a simplicity that drains them of interest, leaving the “world of tomorrow” feeling less vivid than the past it yearns for. By contrast, the glossy scenic design by Derek McLane (Broadway’s Moulin Rouge!) is far more evocative in its rendering of the past, grounding the play in warmth, texture, and the always-present romantic idealism.

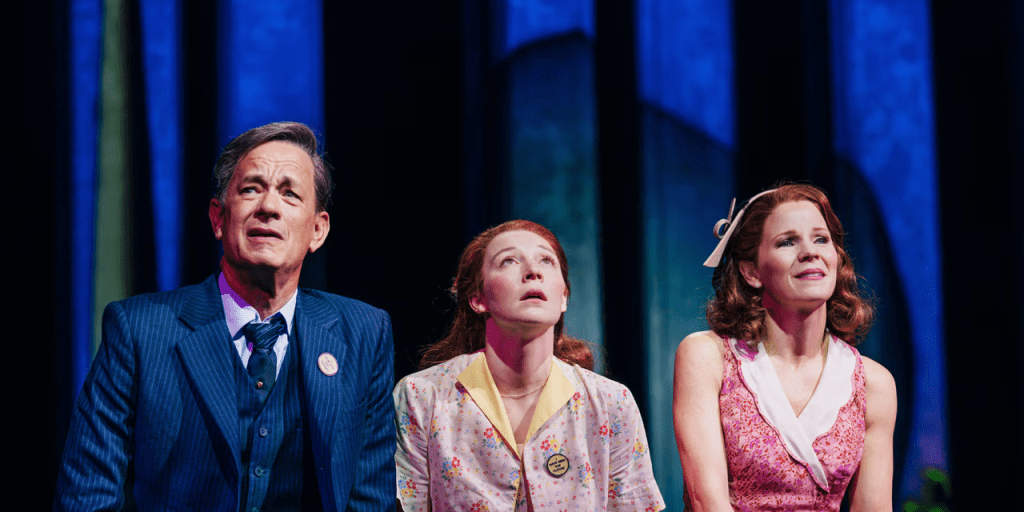

Kelli O’Hara (Broadway’s Days of Wine and Roses) as the well-crafted and put-together Carmen is the emotional anchor of the piece, and she graces every scene with old-fashioned elegance, humor, and an unforced sincerity that recalls classic screen heroines. She feels like a spiritual cousin to Meg Ryan’s rom-com characters, with a dash of Cher’s “Moonstruck” accountable vulnerability. She’s wise, wounded, and open-hearted, almost like the Hanks character in “Sleepless in Seattle“. Her Act Two monologue about her first husband, Eddie, is by far the play’s most emotionally truthful and affecting moment, offering depth and specificity to what might otherwise remain a wistful fantasy. In her conversations with Bert, Carmen becomes both a symbol of the past and a fully realized woman wrestling with the desire to rewrite her own story. And we fully understand his attraction.

Hanks, reversing the familiar dynamic of his romantic roles, is the one sleeplessly pining across time, rather than across a continent. His Bert is earnest, slightly awkward, and deeply human, even as his wealth and technological power stretch beyond comprehension. The framing device, traveling repeatedly between identical hotel rooms in different eras, works theatrically, though the play’s forward momentum can feel as slow and deliberate as a taxi inching its way through midtown traffic. His, and the play’s gentleness, are both the play’s strength and its limitation; the audience must choose to remain engaged, much like settling into a comforting and familiar romantic film streamed at home, rather than a high-stakes drama at the movie theatre.

Supporting performances help lift the piece up, maybe higher than it deserves to be, particularly the feisty and completely engaging Kayli Carter (2ST’s Mary Page Marlowe) as Virginia, authentically nicknamed Sparks, whose energy and sharp intelligence bring a welcome jolt of vitality to that wide stage. Like a well-timed gust of wind during a summer evening, she keeps the obvious romance from drifting too close to cloying or sleep. This World of Tomorrow may not dazzle with spectacle or narrative urgency, but it does offer something unique: a sincere meditation on memory, longing, and the enduring hope that love, like time, might still bend in our favour.