The Broadway Theatre Review: The Queen of Versailles

By Ross

The Queen of Versailles closed on Broadway last Sunday, months earlier than planned and years earlier than anyone involved likely hoped, given the staggering investment behind it. Built on the assumption that the names Kristin Chenoweth and Stephen Schwartz could sell tickets indefinitely, the production instead joins the unfortunate canon of spectacular Broadway miscalculations. Despite Chenoweth’s reliably solid voice and Schwartz’s legacy, this musical arrived structurally broken, ideologically confused, and emotionally tone-deaf — problems that were already glaringly evident during its disastrous pre-Broadway run in Boston. That it still made its way to Broadway feels less like confidence and more like denial.

Sitting there with my jaw dropped unconsciously, I found myself stunned by how profoundly ill-conceived the show was, easily eclipsing even the recent Tammy Faye musical in its misjudgment. Tammy Faye, at least, had moments of craft and a discernible point of view, even if its timing, opening a satirical musical about Evangelical power grabs just after a pivotal federal election, was catastrophically wrong. The Queen of Versailles suffers from a similar blindness to context, but without Tammy Faye’s occasional insight or grace. And much like that final “Sex and the City” film, this Queen collapses under the weight of its own consumption, mistaking the accumulation of luxury for meaning and self-importance for insight. Watching this musical now, centered on a woman’s oblivious financial gluttony and relentless self-mythologizing, feels less like satire and more like a prolonged exercise in audience endurance.

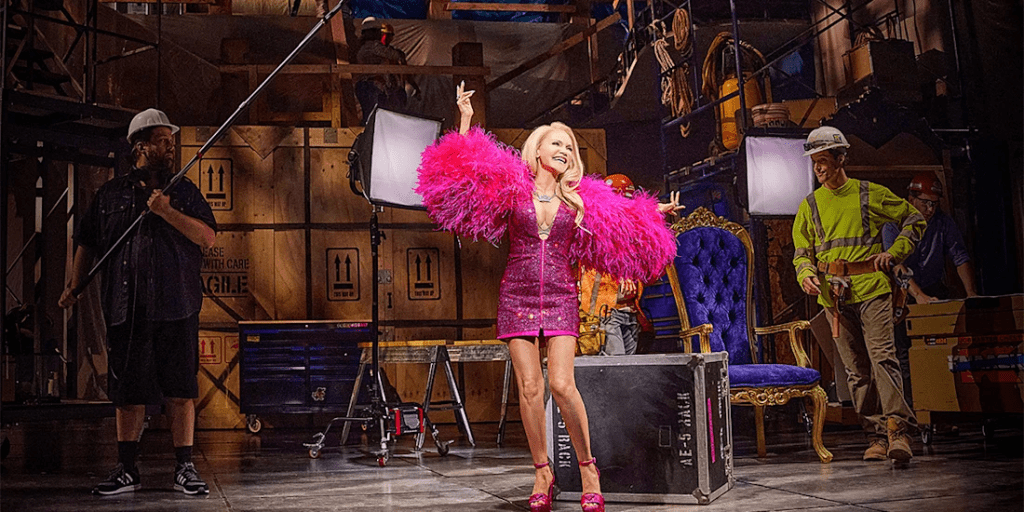

At the heart of the problem is Jackie Siegel herself, and the production’s utter failure to interrogate her. Chenoweth seems oddly unaware (or is she?) of what she’s selling, particularly when she strides onstage as a supposed 17-year-old version of Jackie without a wink, a crack, or any acknowledgment of the absurdity. Offstage, Chenoweth was granted a very public opportunity for a moment of self-correction — a chance to reframe, soften, or rethink — and instead doubled down on the same ill-conceived Kirk narrative, reinforcing the sense that neither performer nor production could see the problem clearly. The show begins with dreams of champagne and caviar, and it ends there too, after financial collapse, tragic personal loss, and public humiliation, with Jackie still clutching her fantasy and insisting, alone in her cavernous house, that “you deserve more.” The line, in a way, is meant for her and her family, but it lands squarely on us.

The show’s political and cultural blind spots are spectacularly gobsmacking, blowing our minds over and over again. Jackie’s repeated insistence that she wants to be “American royalty” is never meaningfully examined, let alone challenged. Royalty for what, exactly? For marrying a wealthy grifter whose business practices echo the very forces hollowing out American democracy? When the production proudly unveils the “biggest screen in America” and splashes Fox News across it, the audience response isn’t laughter-with, but horrified recognition. I found myself watching in a state of frozen disbelief, the same expression I wear when doomscrolling cable news: aghast, frozen, and increasingly incredulous that no one involved saw how this would land.

Directed shockingly by Michael Arden, the one who most beautifully helmed Maybe Happy Ending and Broadway’s thoughtful revival of Parade, some glimmers of vocal beauty are found in the mix, haphazardly. Nina White (ATC/Broadway’s Kimberly Akimbo) and Tatum Grace Hopkins (Broadway’s For the Girls), playing Jackie’s daughter Victoria and niece Jonquil, sing gorgeously, offering moments of sincerity and musical relief. But their characters ultimately function as decorative trim, disappearing emotionally just as the rest of Jackie’s children do. Even the trauma endured by the household staff, including Sofia (Melody Butiu), a housekeeper separated from her own children for years, is brushed aside in a song that exists only to mildly inconvenience Jackie’s party plans. Nothing sticks. Nothing changes. Nothing matters beyond the central figure’s wounded vanity.

The Queen of Versailles is less a cautionary tale than a case study in creative hubris. It mistakes wealth for spectacle, entitlement for aspiration, and obliviousness for charm. What might have been a sharp critique of American excess instead becomes an uncritical celebration of it, arriving at precisely the wrong cultural moment and refusing to see itself clearly. In the wake of its closure, producers would no doubt prefer to blame Broadway’s financial machinery — union costs, rising expenses, the business itself — but that argument rings hollow, a deflection that sounds increasingly like the empty talking points we hear daily from political press briefings: confident, rehearsed, and fundamentally untrue. If Broadway is meant to reflect who we are, or challenge who we’ve become, this production did neither. It merely stared at its own reflection, convinced it deserved a ballroom and a crown (much like another who dominates the doom-scroll news cycle these days). But maybe not the one I’d give.

[…] not because Broadway is “hard,” but because some of these shows simply weren’t good. The Queen of Versailles wasn’t a misunderstood experiment; it was, as I wrote at the time, “a musical so in love with […]

LikeLike

[…] second Broadway outing of the season also feels like a reclamation after the misfire of The Queen of Versailles, a reminder that strong writing, in the right form, can still cut […]

LikeLike