The Off-Broadway Theatre Review: Anna Christie

By Ross

Assembled before our very eyes in the first few moments of Eugene O’Neill’s Anna Christie at St. Ann’s Warehouse, the play barges in with an impressive, kinetic staging crafted by a formidable cast. It steadily steams forward through thematic turbulent waters, and even if the play itself ultimately feels more resonant in parts than as a whole, the framing itself shape-shifts like the ocean, both formidable and dangerous. Directed with clarity and purpose by Thomas Kail (Broadway’s Sweeney Todd), this triumphant revival leans heavily into physical transformation, atmosphere, and emotional excavation, often finding its richest rewards in performance rather than in O’Neill’s sometimes blunt architecture.

Tom Sturridge (Broadway’s Sea Wall/A Life) delivers a fascinating and deeply embodied portrayal of Mat Burke, moving through the space like a broken ape coiled into a defensive, brooding menace. With waves of sudden vulnerability, his hot-blooded physicality does as much storytelling as his well-crafted voice, suggesting a man shaped by violence and longing in equal measure. Matching him with physical authority and vocal weight, Brian d’Arcy James (Broadway’s Days of Wine and Roses) transforms himself compellingly into Chris Christopherson, Anna’s sailor father, finding depth in bluster and tenderness beneath the character’s stubborn moral absolutism. Together, the two men create a combustible dynamic duel rooted in pride, possessiveness, and unspoken fear, and their scenes crackle with tension, especially when they face off, seated across from one another in combative conflict.

But all eyes are on Michelle Williams (Manchester by the Sea; Broadway’s Blackbird), who anchors the production with a strong, well-defined Anna, particularly in her early scenes. Her first reactive boarding with Mare Winningham’s Marthy Owen is especially effective and enlightening. Winningham (Broadway’s Girl From the North Country), in detailed costumes by Paul Tazewell (Broadway’s Suffs), brings a lived-in fullness to her secondary role. She grounds the world of the play with quiet authority and history etched into every line. Though she exits early, never to be seen or heard from again, her stance remains embedded somewhere inside Williams’s Anna. When Anna later speaks of feeling “clean like I took a bath” in the sea air, Williams makes the sentiment that is at the core of the play land with a fullness of meaning. We see how the ocean has become a place of belonging rather than escape, a rare moment where O’Neill’s symbolism feels earned and honest, mainly because of Williams’ gutsy determination.

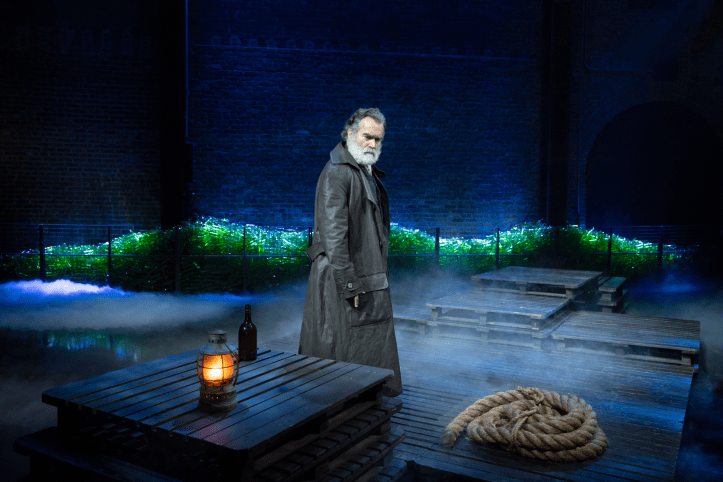

The staging is one of the production’s great strengths. Christine Jones and Brett J. Banakis’s set assembles itself before our eyes from a pile of chairs and platforms into tight ship interiors and worn barrooms where lager and hard liquor flow freely. The space feels constantly in flux, thanks to lighting designer Natasha Katz (Broadway’s Some Like It Hot) and sound designer Nevin Steinberg (Broadway’s The Notebook), mirroring the way the sea flows, and how these characters rearrange their pasts depending on who is listening and what survival requires. A looming steel beam rotates overhead, threatening collapse as the ensemble reconfigures the floor scene by scene, like a balletic crew of masculine seamen reshaping their environment through muscle memory and routine. The green plastic background, however, remains more puzzling. It never fully comes alive as the “old devil sea” so often invoked, and its meaning feels underdeveloped and artificial, rather than symbolic and engaging.

Anna Christie still wrestles, aggressively, with the double standard of sexuality for men and women, laying those ideals bare, mainly because of the richness of its performances. O’Neill’s larger ideas about redemption, identity, and the sea as both corrupting and cleansing emerge unevenly, sometimes landing with blunt insistence rather than emotional accumulation. Yet this production largely transcends those limitations through the rigor of its performances and the intelligence of its staging. What Thomas Kail and this cast achieve is not a reinvention of the text, but a muscular reckoning with it in waves, allowing its wooden fractures to remain visible rather than smoothing them away. It’s solid and seaworthy, making Anna Christie at St. Ann’s Warehouse feel less like a relic revived than a storm weathered. It’s imperfect, bruising, and deliciously shaped by forces larger than the people caught within it, crashing insistently against the social walls that try, and fail, to contain it.