The London UK Theatre Review: End

By Ross

After an exchange of love, tenderly delivered, Alfie states, quite clearly, “I’ve accepted what Dr. Chan said on Friday.” And in that beginning, End at the National Theatre completes David Eldridge’s epic trilogy with warmth, intelligence, and exceptional acceptance. Steeped in extraordinary performances, even if its dramatic temperature never quite rises to the boil, the play digs into the personal choices and desires one might ask of loved ones as we walk, with a sickly shuffle, towards death. Structurally, the play feels like an engagement infinity loop in repeated rhythm. Its tension swings back and forth on purpose, pushed by denial and a desire to reframe, rather than steadily building into something that would grab our heart and squeeze. Moments of revelation arrive, hover in the air, and then recede, returning to a state of being that isn’t connected to reality, creating an experience that is thoughtful, engaging, and tender but often emotionally diffused. Like an amusement park ride that promises an exciting drop but only goes round and around, up and down, without surprise, it never fully delivers the shock or surprise. The play just keeps on engaging in its ideas, without ever really delivering an escalating thrill.

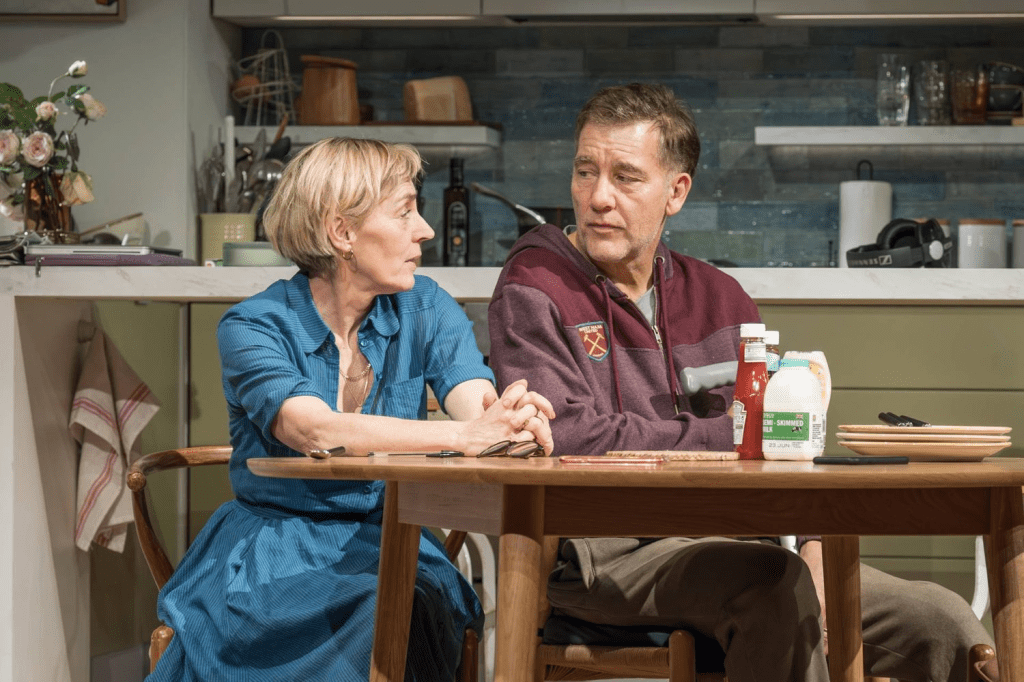

As Alfie, Clive Owen (Broadway’s M. Butterfly) stands beautifully firm while buckling under the tremendous pressure and pain of disease. Saskia Reeves (“Slow Horses“) as his writer wife, Julie, meets his gaze with a generally well-formed honesty. Together, they are, without question, the evening’s greatest strength. Their performances approach a spellbinding quality in their authenticity, rich with shared history and quiet understanding. The ease of their connection is unmistakable, and they find genuine life in Eldridge’s dialogue, even when the material resists momentum. Their love feels real, lived-in, and earned, which makes the emotional restraint of the play all the more noticeable. The ideas explored are poignant and moving, but the way they surface and retreat often drains the tension rather than deepening it.

During the whole one-act play, I couldn’t help but think of another two-hander, ’Night, Mother, a play that announces its stakes and then allows the room to grow hotter and heavier with each passing minute. End, as written by Eldridge and directed by Rachel O’Riordan (The Sherman’s Iphigenia In Splott), gestures toward a similar dread. Julie keeps referencing making and having tea, yet it cools before it ever reaches her cup, much like the play itself. Revelations are spread far too thinly across the structure, teasing and softening, teasing and softening, until the final moments arrive not as a grand rupture but as a gentle exhale. The ending does deliver a sweet and affecting engagement, but it feels like a fizzle rather than a release. We leave touched by the love onstage, but not fully shaken by its End implications. It is a thoughtful and humane piece of theatre, beautifully acted, but one that chooses warmth over fire, and calm over the rising heat of panic, fear, and anger that might have made it unforgettable.