A Frontmezzjunkies Interview: Steven Hao on Directing Bartlett’s An Intervention

By Ross

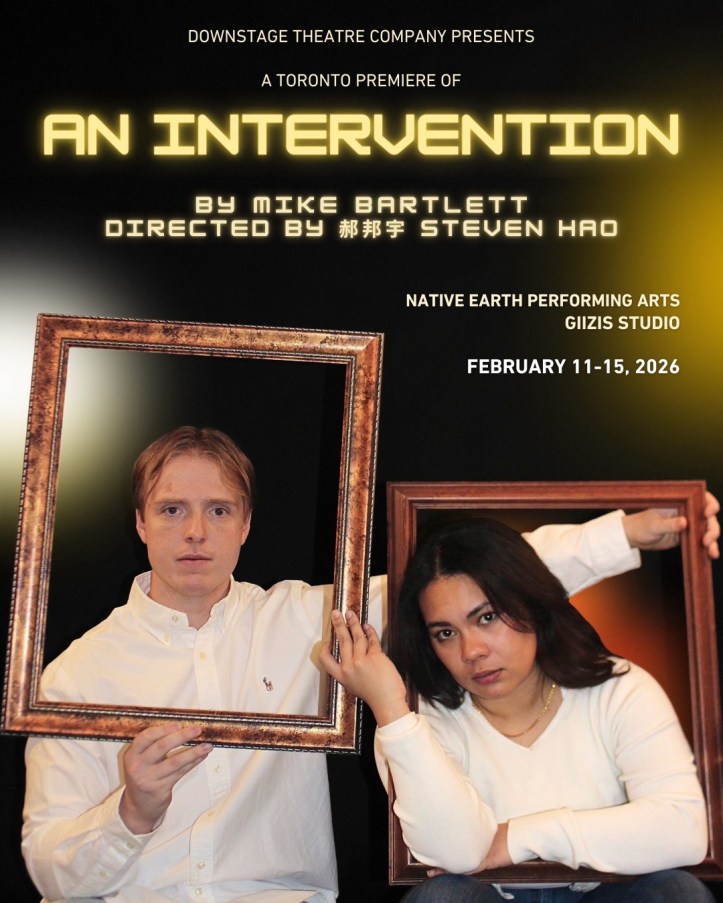

This February, Downstage Theatre Company makes its Toronto debut with the city premiere of Mike Bartlett’s An Intervention, a sharp, intimate two-hander that places a long-standing friendship under a political and emotional microscope. Written by one of Britain’s most incisive contemporary playwrights, the play traces the fallout between two best friends whose responses to the world could not be more different, probing love, ideology, addiction, and personal responsibility with Bartlett’s signature blend of humour and unease.

Directed by Dora Award winner 郝邦宇 Steven Hao, An Intervention stars Jadyn Nasato and Jordan Kuper and runs February 11–15, 2026 (opening night Feb 13), at Native Earth Performing Arts’ Giizis Studio. Known for his sensitive, actor-centred work and his ability to navigate complex emotional terrain, Hao brings a measured, contemporary eye to Bartlett’s tightly coiled script. I spoke with Hao about directing Bartlett’s spare, demanding script, and why discomfort can be one of theatre’s most productive tools.

FRONT MEZZ: An Intervention lives almost entirely inside a single conversation between two friends. As a director, what excited you about working with such a compressed, dialogue-driven structure, and what challenges did it present in rehearsal?

郝邦宇 Steven Hao: I actually really enjoy the compressed structure that is the show! It’s what excited me the most when Downstage first approached me about directing the piece. The compression creates this pressure-cooker-like feeling, and you’re just waiting for it to blow. It’s naked, raw, and intimate, which is very exciting to work on, having just directed shows that were quite large in scale and vision. The challenge, of course, is making sure that the conversation feels alive and that the characters are thinking actively. One of the traps with this show is that without detailed text analysis, the show could easily turn into a 70-minute-long argument, so my job becomes about finding the ebb and flow that is needed to direct these deeply intellectual characters.

FMJ: Mike Bartlett’s writing often refuses clear moral answers. How did you approach staging a play that interrogates politics, addiction, and responsibility without telling the audience what to think?

SH: I’m thinking of the ambiguity as the engine of the show rather than a problem to solve. Bartlett isn’t interested in handing the audience a verdict, so I wanted to make sure my job wasn’t to clarify the “right” position, or make the audience choose sides, but to make every position legible, emotionally grounded, and genuinely persuasive in the moment it’s being argued. If the audience finds themselves agreeing with one character and then catching themselves moments later, that’s just the play doing its work.

FMJ: The play unfolds as an intimate two-hander, with very little distance between the audience and the performers. How did you work with Jadyn Nasato and Jordan Kuper to build trust, rhythm, and emotional escalation within such a stripped-down structure?

SH: From the beginning, the work with Jadyn and Jordan was rooted in trust. It helps a lot that they were already deeply intimate friends prior to asking me to direct this play. The play offers so little theatrical insulation, knowing that the relationship itself had to be the spectacle. We spent early rehearsals off-text, talking through the characters’ shared history and mapping what they know about each other that never gets said aloud. That groundwork meant that once we were on the text, there was a deep sense of permission: to interrupt, to sit in silence, to misjudge each other, and to recover in real time.

FMJ: Mike Bartlett’s writing is often praised for its precision and balance, allowing opposing viewpoints to exist without easy resolution. As a director, how did you hold that tension in rehearsal—especially given Bartlett’s own note that these characters function as “designations for speech” rather than fully realized people—without tipping the play toward judgment or moral certainty?

SH: It’s funny you ask this question. I wrestled a lot with Bartlett’s stage direction at the top of this play, which states that these characters are not people, but rather designations for speech, thoughts, and ideas. I think while it’s easy for Mike Bartlett to write the characters in a way that really was intended for him to ask the question: How do we act ethically and stay human, when the world feels impossible to fix? It would be remiss of me to treat them as just ideas and not people with real feelings, struggles. For me, these characters have to care about what they’re fighting for, and whether if that’s “right” or not, is not for me to decide, my job is not to judge them, but to ignite their engine so that they feel human, and in turn, what I want the audience to feel is that you care about these characters and their ideas, rather than imposing judgement and/or feeling like the play is trying to point you towards a certain way.

FMJ: The play hinges on opposing worldviews rather than heroes or villains. How did you work to keep both characters emotionally legible, even when their positions feel irreconcilable?

SH: With Jadyn and Jordan, the guiding principle was that neither character is arguing an ideology; they’re arguing for their own survival, and a reminder that the reason why they keep coming back to each other is because of the inherent joy they also get out of these conversations. We worked hard to strip away “positions” and instead locate the emotional cost underneath each worldview.

FMJ: What conversations did the play spark for you around activism versus passivity in our current political climate, and how did you navigate moments where humour risks disarming the stakes?

SH: The play sparked ongoing conversations for me about the limits and costs of both activism and passivity. It asks uncomfortable questions: When does disengagement become complicity? When does moral urgency turn into coercion? In our current climate, where visibility, outrage, and political identity are often performative and relentless, the play refuses easy binaries. What Bartlett captures so sharply is the loneliness on both sides of that divide, and how easily love and friendship become collateral damage in the attempt to live ethically.

FMJ: Audiences often leave Bartlett’s work feeling unsettled rather than resolved. What do you hope viewers carry with them after seeing An Intervention, especially in terms of how we navigate disagreement with people we love?

SH: I hope audiences leave An Intervention carrying more questions than answers and conclusions. I personally believe that unease is great because more often than not, it is a productive moment you get to have with yourself: Why am I feeling discomfort? I hope this show provides a chance for the audience to reflect on their own friendships and beliefs! What’s great about this play is that it really does not offer a clear solution for navigating disagreements. In that regard, I think the audience should feel encouraged to think: What would I do in this situation? Instead of a position of feeling superior to the characters, but rather, a place of deep honesty and truth with yourself.