The Stratford Festival Theatre Review: King Lear 2023

By Ross

“It smells of mortality,” this King Lear, as the Stratford Police Pipes and Drums parade us into the opening night of the Stratford Festival in beautiful Stratford, Ontario. I must admit freely that I was thrilled. To be invited to all the openings of this world-renowned Festival is a dream, and I couldn’t be more thankful. Yet, I also couldn’t help but contemplate that moment in 2018, when, after watching The Royal Shakespeare Company’s King Lear at BAM, I surprised myself by thinking that I wasn’t quite sure I wanted another Lear viewing for some time coming. Don’t get me wrong. I love the play, with all its rich unfolding divisions around love, blindness, sanity, and a certain kind of madness that lies awaiting deep inside the sharp illumination of darkness and ego. Yet, this Shakespearian contemplation written with all the complexities of love, duty, and deceit intermingled is not my favorite of the bunch (honestly, I think that might be Macbeth). But it certainly isn’t my least favored either.

Yet after seeing that RSC production at BAM, which starred the incomparable Sir Antony Sher, I watched in awe as it dragged itself forward like an old Cleopatrian relic, spreading itself out slowly and ceremoniously in a way that made me slouch in my seat wishing for bed. That King never fully emotionally engaged, even with the hard-at-work Sher, one of Britain’s most esteemed classical actors, giving it his all. He enthrallingly stated in the program that once you play Lear, there’s really “nowhere else to go, Shakespeare-wise“. The part is a virtuoso solitary climb; a battle against time and importance; a “shouting at, arguing with, a storm.” And what could be better than that? It’s the ultimate human duel with the force of nature and existence, crackling with lighting and fury (as it should be). So it’s no wonder that I found myself, once again, ready and willing to engage, with this text and the trauma that is at the heart of this family breakdown.

My fingers were crossed, as the trumpets signaled us all to our seats. They beaconed us most impatiently, ushering us into the dynamic and expansive Stratford Festival‘s 2023 season with ceremonial aplomb, and I couldn’t be happier. This was the first opening of the season, and the energy of the event was electric, just as it was within those first few moments of this King Lear, with Gloucester, played captivatingly by Anthony Santiago (Citadel’s Of Mice and Men), talking uncomfortably to those men nearby about women and sex; as well as legitimacy and illegitimacy, in such degrading and callous terms. I couldn’t help but squirm inside the deafness of his speech, especially as he boasts about it all in front of his “bastard” son, Edmund, played anti-heroically by the wonderfully charming and talented Michael Blake (Arts Club’s Topdog/Underdog). No wonder Edmund has become the man he shows himself to be; to his father, and to his half-brother, Edger, played touchingly by André Sills (Stratford’s Coriolanus).

With utter diligent determination, this epic “crawl towards death” digs itself into the stark walled stage with clarity and the love of Shakespearean text. Designed with unique and compelling lines and lit boundaries by Judith Bowden (Shaw’s Desire Under the Elms), the impact from that first scene registers undeniably strong, brilliantly illuminated by sharp shards of light designed most impressively by Chris Malkowski (Shaw’s Chitra). It gives structure and significance to the geometric lines of space and power, never letting us disengage from the sanity and insanity of the form and the falling from start to finish. It truly is a brilliantly constructed visual, not exactly matched by the characters in its midst.

Parcelled in that frame, this King Lear is determined, mainly because of the casting of Paul Gross (“Slings and Arrows“; Stratford’s Hamlet) in the title role. He enters strong and vital, powerful and emotionally cut to the bone. He doesn’t look like a man ready to give up his throne, yet for some reason, he has come to this untimely decision, and I couldn’t help but lean in wondering how this will unfold. This becomes the question of the night. How will this Lear develop, giving clarity and a deeper understanding to his untimely rationale of departure and dependence? Will he let us in to see the “Why now?” that is at the heart of his King? With an impressive head of long white hair, Gross finds an engagement inside the text that delivers expressively, but maybe not entirely finding the answer. It’s smart and clear-minded, yet he doesn’t, at least in the beginning, give off an air of being “old before your time“. Yet it’s there, slowly, and with a tense heart-pounding pulse and a clutching of his chest. It lives somewhere in the pained heart; the idea that this man knows a thing or two about mortality and disease, whether conscious or not, and needs something (or someone) else to help him manage, to take hold, without the losing of his regal form, and without having to ask for it directly. Pride is a formulation that doesn’t serve this King well, and arrogance. That we all know.

The historical framework of Gross’s return to Stratford is one for celebration and excitement. And I was totally there for it from the moment I read of his casting. The construction seems sublime and timely as Gross played Hamlet on this very stage back in 2000. That appearance mimicked one of my all-time favorite television shows, the Canadian “Slings and Arrows.” The series unearthed a fascination with and an understanding of the three powerhouse roles for an actor: Hamlet, Macbeth, and, more importantly, King Lear (I would have said ‘male actor’ but I’m hoping that gender specificity is receding somewhat, especially after watching Glenda Jackson give us a Lear to remember). The television show relished over three seasons the idea of exploring the three stages of man, one per season. (If you haven’t seen this brilliant and funny look at art and commerce within the world of Shakespearean Summer Festivals, find it immediately and dig in.) Romeo and Hamlet mark the beginning of engagement, Macbeth takes on the middle years with a conflictual urgency, and King Lear, one of the greatest parts for an older actor, unleashes the madness in the grand finale. It seems Gross has decided to skip the Scottish play and run headlong into the storm that is King Lear. For that, I am intrigued. I couldn’t help but wonder, what does he have in store for us after all these years away.

As directed by Kimberley Rampersad (Shaw’s Man and Superman), the play somehow doesn’t find its way to the emotional core, seeming uncomfortable and surprisingly traditional in its unraveling of the inherent drama. It does hold some intellectual grace, and a great deal of found humor within its delivery, yet it somehow rolls in like a controlled storm without a clear unique fierce vision. Through its epic arc of realization in the face of betrayal, this production somehow struggles to clarify itself, attempting to give a darker meaning to blind needy arrogance and narcissism, yet never really unpacking its true personal ideology. It plays itself so straightforward with a direct clarity of the language, spinning the traditional yarn gracefully, but I wondered where this production’s true underlying vision lies. Or is it blindly wandering through the heath without a strong hand to guide it? I wanted a compelling vantage point to usher us through the known wild storm of Lear and into something fresh and exciting, one that matched the wild inventiveness of the stage and its structural illumination. Yet it feels flat and formulaic, even in its fine standardized telling. Don’t get me wrong, for the most part, it played itself out with a textual honoring that unpacks Lear’s slow mental decline well, even inside the youthful appearing body of the old man. But I wanted some contextual understanding that wasn’t so obvious and laid out. Something that made this Lear crackle like the storm that is coming.

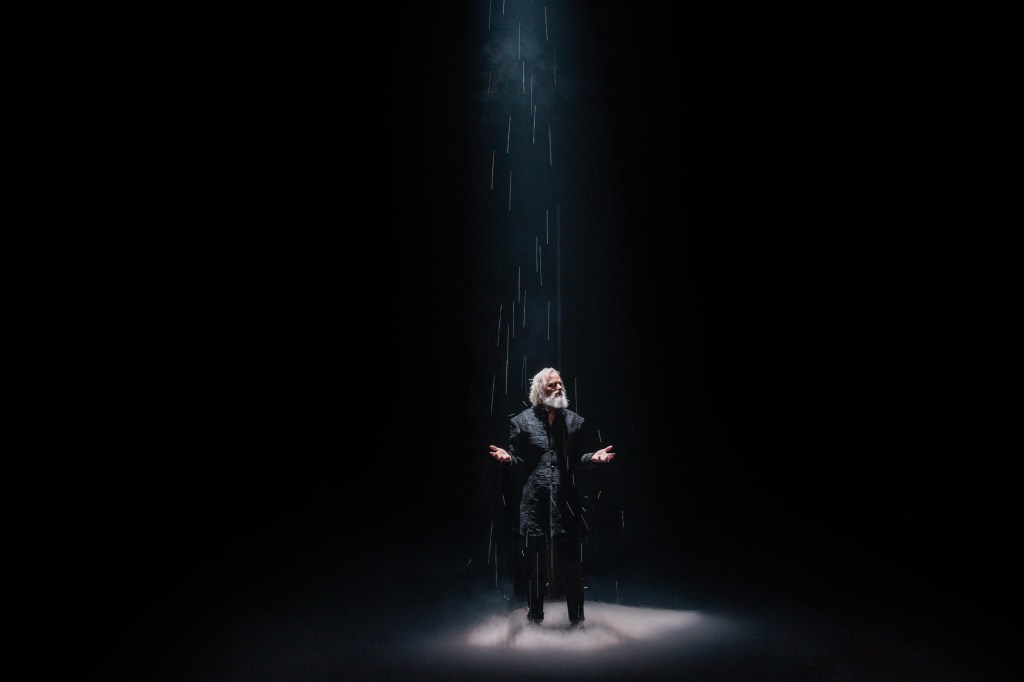

The strongest symbol of its unfortunate undoing is the visual impact of the storm. Years ago, when I was in my teens, I saw a production of King Lear that helped solidify it as one of my favorite Shakespearian tragedies. It starred Peter Ustinov standing center stage at the same Festival Theatre (1980, directed by Robin Phillips), with a torrential rain and wind storm blasting him from every direction, almost ripping him apart. It was a powerful moment that stayed with me, but nowhere in this current production did I get the sense that Gross’s Lear could actually be blown to bits. The ‘rain’ did fall down on him, steady and straight, dampening his hair and his spirit, but there was no danger in it. No wind. No uncontrollable gusts. Just a steady stream of ‘rain’ that fell in a controlled small pool of light. Nothing to be afraid of here, I thought.

It has been said that Lear is somewhat of a paradox. He’s known for his wild and windy battles against the storm of dementia, but at the beginning of this tale, he feels technically sane, looking strong and centered in his proud but narcissistic insolence, even as it is clear that the stance is highly misguided. As portrayed by the compelling Gross, his almost youthful arrogance struck true, fortified by an absurd desire to hear only praise and levels of love that makes no sense. His older two “pelican daughters“, portrayed by the stern Shannon Taylor (Crow’s Uncle Vanya) as Goneril, and Déjah Dixon-Green (Grand’s The Penelopiad) as the violent secondary Regan, willing play the insincere game, showering him measurably with adoration that borders on the ridiculous. But Lear doesn’t hear that quality, he only registers the over-wrought deceptive venerations and digs his heels in with delight. The older sisters understand their father’s prideful need for idolatry, and praise him with words that are actually too grand and quite foolish in idea and theme. They stand, without any backstoried clarity (something that I blame on the interesting new play, Queen Goneril after seeing it at Soulpepper. I will always now look for hints and side glances of the problematic familial history, trauma, and the reasonings for these two older sisters’ heartless cruelty. But I wasn’t going to get that here, as the subtext wasn’t available to be seen). They are dolled up in detailed costumes designed confusingly by Michelle Bohn (CSC’s A Four Letter Word) that appear initially as somewhat symbolically bold and classical, yet unfurl and start to feel somewhat weird, haphazard, and unfocused, bringing at least one-time giggles from the audience because of one ‘funny thing happened on the way to the forum’ yellow frock. I just couldn’t understand the choices made in those sisters’ getups, just like I couldn’t fathom some of their overly melodramatic responses.

Standing in the background throughout, struggling in her own way, is the favored daughter, Cordelia, the youngest and most clear-minded, played somewhat flatly and blandly by Tara Sky (Soulpepper/Native Earth’s Where The Blood Mixes), who decidedly fails to play up to the arrogance and desperate needs of her father, the King. It’s an act of bravery, in a way, believing her unquestionable love will be seen, felt, and known by her father, but she is not, finding herself cast off, thrown away, betrayed most callously by her honesty and candor. The tides of joy turn dark, like white fluffy clouds that quickly darken and turn ominous with the changing of the wind. Dementia and madness start to blow in, and we watch as that seed takes hold and twists the King’s form and face into something quite scary, and then sad and despondent. The moment doesn’t actually fully resonate, but as she is packed off to France, we sit wondering what just happened, and why it never felt truly heart-breaking.

The Earl of Kent, played with an undetermined tone of voice and character by David W. Keeley (Stratford’s Coriolanus), attempts to stand up to the King, defending Cordelia’s public declaration of love for her father, but to no avail. He, like her, is not heard through the stubborn barriers that enclose this King. He and Cordelia are chastised and ordered away, and the two elder eager daughters take control of the kingdom, gaining power over all, including their father. Why the King doesn’t recognize Kent when he returns to serve him I can’t say. He has changed nothing about his appearance, yet we are instructed to believe, and so we shall. With some effort.

This is not going to end well for the old King, but as he brandishes his bullying privilege over Goneril and her court, we struggle to get under the skin of his or her predicament. Something about that first formulation of banishment and dismissal didn’t register in the way it somehow should have. We must almost instantly align ourselves with the discarded pair, or it seems the reformation doesn’t really stand a chance to fully emotionally engage. Cordelia is scantily only given that initial scene to connect to our collective heart, yet standing there, in her oddly fitted prom dress, our bond with her falls flat at her feet, hobbling the future traumatic undoing mainly because of this detached uneven first engagement.

Something isn’t sitting right, yet we know how this will run its course. We see it from the very beginning, and although King Lear in the hands of director Rampersad hasn’t fully captivated us or made us understand the director’s vantage point, the engaging Gross works hard to create a father and a King that is proud, argumentative, and sharp as a claw. We know, or at leastbelieve that the torturous journey through the wastelands will somehow cake his frame with mud and bruises, but somewhere along the path, we are challenged to see it, even though it never fully formulates itself strongly. His progression to his undoing staggers forward sneakily, with the wonderfully sly Fool, played with clever intuition by Gordon Patrick White (Neptune’s The Devil’s Disciple) delivering the truth through his sharply barbed tongue. It’s a wonderfully detailed deliverance, but I would have favored some more physical affection between the King and his fool, well, from anyone to be honest, as the play fails to touch and be touched with any kindness and connection, even as he derails himself against the approaching storm that never really materializes.

In the first and only subplot to be found in this Shakespearian tragedy, the bastard son Edmund (Blake) is also quite the devious and deceiving child. He orchestrates a well-thought-out and structured plot to forge mistrust between his father, the Earl of Gloucester (Santiago) and his legitimate son, Edgar (Sills). Paralleling the familial betrayal between parent and child, the deceitful Edmund finds a dark sensual stance to play out his cruel plot with ease and a coolness that registers, flying forward with heartless glee. He throws his half-brother underfoot, forcing the man to flee in a confused flurry of accusations, only to find himself later leading his blinded father through the same wasteland of distrust and deceit. Blake’s charming approach to deception is captivatingly engaging, selling the moment, even if initially Sills’ approach to Edgar doesn’t feel fully formed. At least not in those first moments. It deepens as the anguish builds.

Now both fathers find themselves caught in the storm of misguided betrayal, but both are there, wandering through the wasteland unprotected solely because of their own doing and arrogance, believing in lies and flattery, even when it goes against their better judgment. The Earl of Gloucester has also been dutifully wronged, cut down, and gruesomely gored by the same plot and ploy, but we feel we understand, at least a little, why his illegitimate son would hate him so. (It isn’t so clear why Regan would though.) The destroyed son leading his blind accuser through the wasteland is one of the more fragile and clearly intimate moments of kind compassion seen between child and father. The image elevates the pain that has been forged by the cold-hearted damaged child, Edmund. Is this what happens when mothers are not anywhere to be seen?

It is said that with Lear, you do it big, or go home. But delivering a revisitation of the compelling tale without a clear answer to the “why now?” question, both in terms of the production and the characterized stepping down of this King Lear, beyond some obviously broad strokes, becomes the central problem and obstacle. Returned from her banishment, Cordelia sits at the bedside of the found mad Lear, his sad confusion registers, but not completely. It’s painful to watch the struggle, as we know what the inability to recognize means, and what is in store for the poor upset former King as he lovingly remembers both his favorite daughter and his loyal Kent. The look is all the more engaging knowing how much he has lost out of pride and fury.

Yet when the King returns with her lifeless body, we are surprisingly not moved. The production didn’t lead us in deep enough to engage with the dark well of tragedy and sense of loss. Gross’s Lear nods himself off into death, unceremoniously, leaving us to wonder where our emotional pain and connection has gone. It’s sad that we aren’t that moved by Rampersad’s King Lear, even though it gives some insight metaphorically to the blind and foolish, especially through its diligent delivery of the text. But as a whole, it failed to sit heavy nor forcible in my heart. No tears of grief came to my eyes when the struck-down King sees the ridiculousness that lived inside his ego, and the destruction it has brought forth. And that’s a shame, as there is something clever inside Gross’s return to the stage, and his interpretation of his damaged and dying King Lear.

[…] death, thankfully, even if that Friar, played lovingly by Gordon Patrick White (Stratford’s King Lear), suggests a “Romeo and Juliet” plot device that makes us wonder: Did he learn nothing […]

LikeLike

[…] the wayward Pierrette Guétte Guérin, played tough by Allison Edwards-Crewe (Stratford’s King Lear), sister of Germaine who leads a shameful life working in the club of her boyfriend. This is a step […]

LikeLike

[…] is André Sills, a member of the acting company for nine seasons, this year playing Edgar in King Lear and Don Pedro in the miraculous Much Ado About Nothing. Other key roles include the title role in […]

LikeLike

Rampersad s directing was weak

I found. The characters move about on stage randomly and more than not I was watching an actor’s back with others hidden from my view…worse blocking I have seen in my life…

LikeLiked by 1 person

will there be dvd?

LikeLike

[…] court of the Duke of Illyria, Orsino, played big and glorious by André Sills (Stratford’s King Lear), yet all the while serving him, Viola, as Cesario, falls hopelessly in love with the Duke. Beyond […]

LikeLike

[…] of The Lord of the Rings or Game of Thrones, thanks to costuming by Michele Bohn (Stratford’s King Lear), the composer Njo Kong Kie (TPM’s The Year of the Cello), and sound designer Olivia Wheller […]

LikeLike

[…] and ear by Tim Carroll (Shaw’s A Christmas Carol) and Kimberley Rampersad (Stratford’s King Lear). They, and the cast, deliver the glorious goods with expert grace and care, weaving in the […]

LikeLike

[…] with the modern-day well diviner, Royland, played engagingly by Anthony Santiago (Stratford’s King Lear), Morag’s network of friends feels inspiring and emotionally true. It’s when it flies […]

LikeLike

[…] Glenda Jackson’s Lear on Broadway, The Royal Shakespeare Company’s King Lear at BAM, and Paul Gross’s King Lear at the Stratford Festival, but the urgency in its efficiency rarely gets in the way of its […]

LikeLike

[…] Jackson’s Lear on Broadway, The Royal Shakespeare Company’s King Lear at BAM, and Paul Gross’s King Lear at the Stratford Festival, but the urgency in its efficiency rarely gets in the way of its […]

LikeLike

[…] Bluma Appel Theatre, TorontoFirst Preview: January 18, 2025Opening: January 23, 2025Starring: Paul Gross, Martha Burns, Mac Fyfe, Hailey GillisPlaywright: Edward AlbeeDirector: Brendan […]

LikeLike

[…] as Shirley Wershba; and my favorite Paul Gross (“Slings & Arrows“; Stratford’s King Lear) as William F. Paley, the sharpness has remained intact and neatly defined. There is also the […]

LikeLike

[…] stage itself almost overflows with Stratford talent, even in the smallest of secondary roles, like André Sills as Ross and Emilio Viera as Lennox, riding their metallic horses with an authentic biker edge that […]

LikeLike

[…] enough tap dancing, choreographed by the show’s director, Kimberly Rampersad (Stratford’s King Lear), to overly fulfill any requirements one might have for this delicious, delirious, delightful dream […]

LikeLike

[…] and hope, and Pearl Cleage’s masterpiece, directed by Kimberley Rampersad (Stratford’s King Lear), promises to capture the true spirit of an era that changed everything. With soulful music and […]

LikeLike

[…] well by Kimberley Rampersad (Stratford’s King Lear), the play is a complex story of this family of friends, richly painted in the air around them. We […]

LikeLike

[…] of General Henry Waverly, played with heart-tugging sincerity by David Keeley (Stratford’s King Lear), gives the first real lump-in-the-throat moment, as he prays for a better world in the midst of […]

LikeLike