The Stratford Theatre Review: Ibsen’s Hedda Gabler and Shakespeare’s Cymbeline

By Ross

Tom Patterson was a man of great vision. He was a Stratford, Ontario-born journalist who founded the Stratford Festival, then called the Stratford Shakespearean Festival, the largest theatre festival in Canada. He saw something in this small town that maybe no one else saw. Now his namesake theatre, the lovely Tom Patterson Theatre is home to two ultra-captivating and illuminating revivals, shedding light on two classics that sometimes can overwhelm and conquer others. But not here. Both productions; Shakespeare’s Cymbeline and Ibsen’s Hedda Gabler, are epic and transformative, digging into complex themes steeped in intrigue, with battles for control and power over others at their core. And both are delivered forth with a vision and preciseness that astounds and illuminates, ricocheting light and understanding that is seldom felt when watching these timeless tales.

Directed with a magical force of nature by Esther Jun (Stratford’s Les Belles-Soeurs), Shakespeare’s complex and daunting Cymbeline, contains plot points that could easily overwhelm and entangle those in charge. They twist and envelope, like tree roots in the earth, but here at the Stratford Festival, Jun expertly finds a way to unravel and expand the many threads that are so thick and entwined. So clear and determined is her stance that the resolution in the final scene, which generally feels endlessly complex and never-ending, is greeted with clever wit, so much so that the main queenly character voices the overwhelming onslaught of information with an exasperation that almost every audience member can fathom and engage with. Yet we are in it, giving ourselves over almost immediately after the first whispers that come within the smoke.

“Oh lady, weep no more,” we hear, tunneling in from the depths of mystic destruction, as the play pulls us under its spell, thanks to the other-worldliness of both Jupiter, played by Marcus Nance (Stratford’s Frankenstein Revived), and Philarmonous, the Soothsayer, portrayed by Cynthia Jimenez-Hicks (Neptune’s The Play That Goes Wrong). We are enraptured in those first sharp strains of white light, detailed and dynamically delivered by set and lighting designer Echo Zhou (Tapestry Opera/Crow’s Rocking Horse Winner), and we bow our heads to their power.

Based on parts of the Matter of Britain, the dense legends that focuses their eye on the early historical Celtic British King Cunobeline, this Shakespearian tragedy (although some refer to it more as a romantic comedy) is crafted and ushered forward with full-blown epic style, worthy of a stage production of The Lord of the Rings or Game of Thrones, thanks to costuming by Michele Bohn (Stratford’s King Lear), the composer Njo Kong Kie (TPM’s The Year of the Cello), and sound designer Olivia Wheller (Factory’s Here Lies Henry). It feels as powerfully big and dense as its source, legendary and mystically, while unpacking emotional truths that feel authentic and human.

The gender shifting from King to Queen Cymbeline, played majestically by the always fascinating Lucy Peacock (Stratford’s Three Tall Women), now married to the evil conniving Duke, portrayed by Rick Roberts (Stratford’s R+J) in full fiendish delight, finds weight and credence in their mutual unraveling, dismantling concepts that go far beyond even Shakespeare’s grand and complex ideas. Emotionally centered around the secret marriage between the Queen’s daughter, Innogen, sharply portrayed by Allison Edwards-Crewe (Stratford’s Much Ado About Nothing), and the worthy, but low-born Posthumus Leonatus, dutifully played by Jordin Hall (Stratford’s Grand Magic), their act of love upends the court, as Innogen was orchestrated to wed the Duke’s only son, her stepbrother, Cloten, played flamboyantly by Christopher Allen (Tarragon’s Redbone Coonhound), and rally the land against the tribute-demanding Roman Empire.

And that’s just the beginning of this complicated upheaval. By telling the interwoven tale of love, forgiveness, and the interconnectivity of all, “like the roots of trees“, Stratford’s Cymbeline, overflowing with the most talented of actors, magnificently finds clarity, as it speaks to the world at large. Moving through the in-humanity (and humanity) or trauma, war, misogyny, decolonization, and this abstract code of patriotism and nationalism, the cast; particularly the incredible Irene Poole (Stratford’s Les Belles-Soeurs) as the mindful servant Pisanio; the seductive Tyrone Savage (Stratford’s Love’s Labour’s Lost) as the Roman schemer, Iachim; and Jonathan Goad (Stratford’s Spamalot), Michael Wamara (CS/Obsidian/Necessary Angel’s Is God Is), and Noah Beemer (Stratford’s A Wrinkle in Time), as the three honorable cave dwellers, Berlarius, Guiderius, and Arviragus, dig into the melodrama, as well as the authentic emotional attachment required to make this 3-hour play tick forward and engage. The play is unpacked with the boldness of separated lovers and stolen sons, imprisoned and banished, seduced and assaulted for chastity and heroic honesty.

Faith plays a tenuous part in the unraveling at hand, with the two lovers forced apart by parents unwilling to hear or engage, paralleling the soon-to-be-seen Romeo and Juliet, right down to the poison that isn’t exactly deadly. But the true art in this presentation is how smoothly and wisely it moves forward through the difficult web of plots and failures. The more seasoned company members know how to find the deeper subtleties within that knotty text, while the newer, younger members sometimes struggle with the emotional complexities tied within, but only slightly and in comparison. Yet it comes together, binding us into the ideas of forgiveness, compassion, and understanding, even as we swirl alongside the Queen in those last few moments of untangling and debriefing.

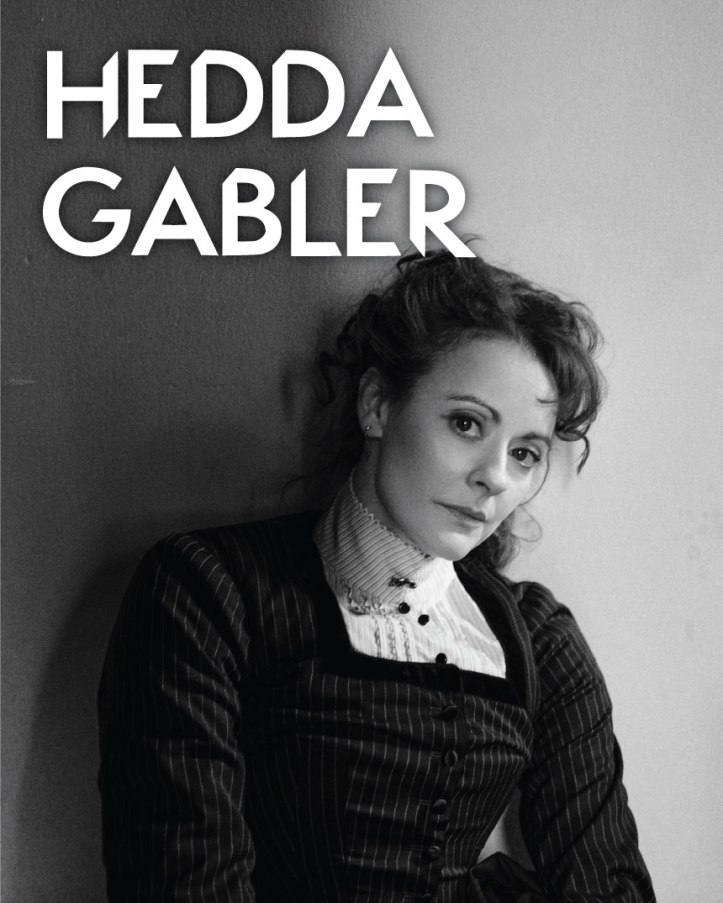

In the same manner that Jun orchestrated a compelling and understandable Cymbeline, director Molly Atkinson (Shaw’s Prince Caspian) unwinds the detailed Henrick Ibsen’s Hedda Gabler with a gentle force worthy of the epic guns unloaded and lent. Utilizing a compelling new version by Patrick Marber (“Notes on a Scandal“) from a literal translation by Karin and Ann Bamborough, this Hedda carries a bitter rage that rarely stays hidden or held but is casually shot out with a direct aim and purposefulness by a privileged beauty used to getting her way. Sharply defined by the wonderful nuanced Sara Topham (RTC/Broadway’s Travesties), Hedda, if she has to suffer in any way, shape, or form, will not do it in silence or on her own. Her boredom burns her from the inside out, shifting the light of frustration on two pistols in hand, fired casually at anyone she chooses to play with or against.

Dressed impeccably by set and costume designer Lorenzo Savoini (Soulpepper’s De Profundis: Oscar Wilde in Jail) and drenched in epic light and shadows by designer Kaileigh Krysztofiak (Soulpepper’s Wildfire), the malice and rage find their home in the bare room and the precise stitching of the fabric of her creation, pulled at by outside passion, betrayal, devotion, and internal disappointment. Hedda is trapped, happily at one time by her father, but more then unhappily by her husband, the loving Tesman, portrayed simply and compassionately by Gordon S. Miller (Stratford’s Grand Magic).

Their marriage is one-sided and corrupt, created simply because Hedda felt it was time.Now, trapped in a marriage and a house that she does not want, feeling the mistake in every bone of her bored body, the soul of Hedda Gabler, now Hedda Tesman, the married woman, believes herself to be more the regal father’s daughter than her intellectual husband’s wife. She was once the detached privileged woman who enchanted the men of this town with her beauty and cool exterior, but now, disturbed by and within her marriage, she finds herself caged in a new house that, while being more extravagant than they can really afford, “smells like old lady” and death. And it will never bring her any contentment unless she seizes control.

Backed by a compelling soundtrack crafted by composer Mishelle Cuttler (Arts Club’s Someone Like You), the unbearable heaviness of her new life is dragged out slowly and cautiously, noted and displayed in the photos of a honeymoon that was more trying than passionate. The housekeeper Berta, played with a great attention to hesitant details of subservience by Kim Horsman (Stratford’s A Wrinkle in Time), and Auntie Juliana, meticulously portrayed by Bola Aiyeola (Stratford’s Les Belles-Soeurs), showcase a realm and stature that Hedda can not tolerate. Newly married, unhappy, yet brilliantly bored and frustrated, this power-hungry and ultimately powerless Hedda finds silly pleasure in manipulation, cruelty, and belittling others, but on a more complex terrain, twisting and torching the hearts of women like Mrs. Elvsted, played compassionately by Joella Crichton (Stratford’s Wedding Band).

It’s shocking that people like Mrs. Elvsted keep returning to the abusive parlour, as if they might be greeted by a more mature and caring soul, but that kind of punch is rarely served here honestly. Other women are playthings to this Hedda, as it is clear to her that they hold no real power over anything that matters. Judge Brack, played to subtle perfection by Tom McCamus (Soulpepper’s King Lear/Queen Goneril), on the other hand, holds a triangular association to something more akin to excitement and advancement. She adores the offensive and defensive fencing that occurs in the presence of these self-important powerful men, particularly McCamus’ deliciously delivered Judge who never fails to find the base truth. But her passion is completely enflamed by the wildness and intellectual freedom that lives, drunkenly, inside Lovborg, played compellingly by Brad Hodder (Mirvish’s Harry Potter…). It’s so connected to her personage and her power that it engulfs her focus, and she must either control it by having or destroying its nature. There are few in-betweens.

Topham’s Hedda carries cowardice hidden just below her haughtiness magnificently, masked by a bravery that doesn’t exist authentically inside her. It appears she holds herself tall and determined, but only if she feels she has the upper hand on those around her. She’s desperate and impulsive, selfish and ungrateful. Her true calling, as she tells us with a laugh, is to “bore myself to death“, with a stance that is defiantly fueled by rage, fear, jealousy, and helplessness.

She tests the waters of her sweeping control, trying to distract and entwine. Yet, when she discovers that her ability to enthrall has evaporated before her very eyes, thrown to the sidelines by the man she thought she had unlimited hold over, that demise is overwhelming. Everything she believed in and held on to just went up in smoke, granting us an ending that is as sharply defined and shocking as it is beautifully staged. There is no saving in this space for her, and even though the last line, delivered almost too casually by the Judge lingers in the complicated air feeling cold, distant, and detached from emotion, the overall darkness cuts sharp and true. It hits like an angry Hedda slap out of nowhere, in a way that this play hasn’t hit in a long time. Burned from the act that just played out before us, the sneak bullet attack in a way, fires out into our souls without warning. “I can’t live like the others,” and so she doesn’t. That idea, and the way this Hedda takes control of her one parloured arena, gets embedded in our hearts as painfully as it does her temple, leaving its mark and its emotional disturbance for us all to carry home with us.

For more information and tickets, go to the Stratford Festival website, or click here.

[…] of the Festival’s Langham Directing Workshop, will direct, after such recent successes as Cymbeline, Les Belles Soeurs and Little Women at the Festival and Kim’s Convenience, which she staged […]

LikeLike

[…] the iconic playwright himself, Arthur Miller, played powerfully by Tom McCamus (Stratford’s Hedda Gabler), rise and engage with that roomful of Chinese actors, we can’t help but lean in with utter […]

LikeLike

[…] calls out to her distracted husband, captivatingly well-played by Rick Roberts (Stratford’s Cymbeline), as Edward Albee’s aggressively engaging play, The Goat, or Who is Sylvia? revs itself up to […]

LikeLike

[…] by Josue Laboucane (Stratford’s Much Ado About Nothing) and Caleigh Crow (Stratford’s Cymbeline). There are also some well-choreographed dance sequences that feature dream-like sequences to the […]

LikeLike

[…] with a casual nudging help from set and lighting designer Echo Zhou 周芷 (Stratford’s Cymbeline), sound designer Chris Ross-Ewart (Coal Mine’s The Sound Inside), and dramaturg Yizhou Zhang […]

LikeLike

[…] into a television studio kitchen, lit authentically by Echo Zhou 周芷會 (Stratford’s Cymbeline) with a solid sound design by Thomas Ryder Payne (Crow’s Wights) and a sharp video design by […]

LikeLike

[…] swift and joyous, with the final topping of reverse fortune arriving in the form of Jaques de Boys (Evan Mercer), another brother to Orlando and Oliver, informing all that Duke Frederick has also found his way […]

LikeLike

[…] and beautiful Queen of Sicily, played to marbled perfection by Sara Topham (Stratford’s Hedda Gabler), who carries herself with an impressive physicality carved with innocence and honor. But the true […]

LikeLike

[…] inhabited emotional road, enriched by a solid sound design by Olivia Sheller (Stratford’s Cymbeline) and musical compositions by Allison Lynch (Theatre Calgary’s The Scarlet Letter), that […]

LikeLike

[…] the vocal playfulness, courtesy of sound designer/composer Olivia Wheller (Stratford’s Cymbeline) and choreographer, Stephen Cota (Stratford’s Frankenstein Revived). The moment carries with […]

LikeLike

[…] All are on full peacocked display here, thanks to director Esther Jun’s (Stratford’s Cymbeline) focused fortitude, delivering the required energy and presence to occupy the floral bows and side […]

LikeLike

[…] Orjalo (Stratford’s London Assurance) Hermione, Menlaus; and Sara Topham (Stratford’s Hedda Gabler) as Adegiale, Helen, Cowering Woman, (Diomedes); stand tall and dynamic, delivering a powerful […]

LikeLike