The TIFF Film Review: Nia DaCosta’s “Hedda” & Arnaud Desplechin’s “Two Pianos“

By Ross

At this year’s Toronto International Film Festival, I found myself watching two films that seemed, curiously, to be in conversation with each other. “Hedda” and “Two Pianos” — vastly different in tone, setting, and scope — both revolve around stunningly attractive, gifted narcissists whose self-regard consumes the people around them. Both films are visually exquisite, elegantly costumed, and filled with moments of emotional precision from their supporting players. Yet what united them most was how deeply and dangerously their directors seemed to have fallen in love with their terrible protagonists — so much so that they forgot to notice how cruel they could be to those around them.

As a psychotherapist, I tend to watch narcissists on screen with a mix of fascination and skepticism. They are irresistible characters, after all — glamorous, unpredictable, and fragile in their grandeur. But what both “Hedda” and “Two Pianos” reveal, perhaps unintentionally, is how easily artists fall under the spell of such characters, mistaking charisma for complexity and charm for depth. Watching both films in close succession, I felt I was witnessing not so much two stories of human unraveling, but two directors seduced by their own creations.

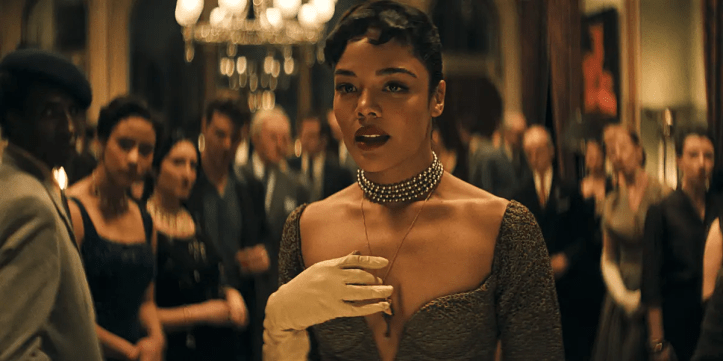

In this film adaptation of Henrik Ibsen’s epic play, Tessa Thompson (“Passing“) delivers an awkwardly mannered performance as the iconic heroine, Hedda, now reignited in a lush, modernist frame that never truly comes together. Transplanted to mid-century England, director Nia DaCosta (“Candyman“) fatally falls for her Hedda, head over heels, like all those around her, delivering her to us like a delectable gift that no one could deny. DaCosta’s elegant vision suffocates under its own lavish admiration; We’re meant to feel Hedda’s despair, yet instead we grow more uncomfortable with each cruel trick she decides to make.

The cinematography by Sean Bobbitt (“12 Years a Slave“) is ravishing, with the lighting catching her every glance like a dash of lacquered gold on a silver platter. Yet the performance, for all its strange poise, plays more like a “pretty Disney villain” than a woman trapped by circumstance or psychology. The audience I sat with — and I include myself here — couldn’t help but giggle, not because the film is comic, but because the self-seriousness of Hedda’s cruelty became absurd. It’s as though the film (and the director) fell in love with her beauty and forgot that beneath it lies something genuinely monstrous. We never quite believe anyone would tolerate her selfishness, and so her tragedy evaporates into stylized posing.

That imbalance reaches its peak in the film’s treatment of Eileen Lovborg, a gender-swapped reimagining of Ibsen’s doomed genius. Nina Hoss (“Tár“) plays her with deep inner conviction — you can see the tension and sorrow beneath her restraint — but she’s betrayed by the film’s set-up, script, and bizarre, unflattering costume, courtesy of designer Lindsay Pugh (“The Marvels“). Dressed in an ill-conceived black-and-white gown that looks more like a visual joke than a wardrobe choice, she becomes a caricature at precisely the moment she should be breaking our hearts. The laughter that rippled through the audience during her big scene said it all: here, design undermined drama. It’s a shame, because Hoss’s work is superb otherwise, as is nearly every secondary performance in the film. If anything, the ensemble is what keeps “Hedda” from collapsing entirely into its own reflection.

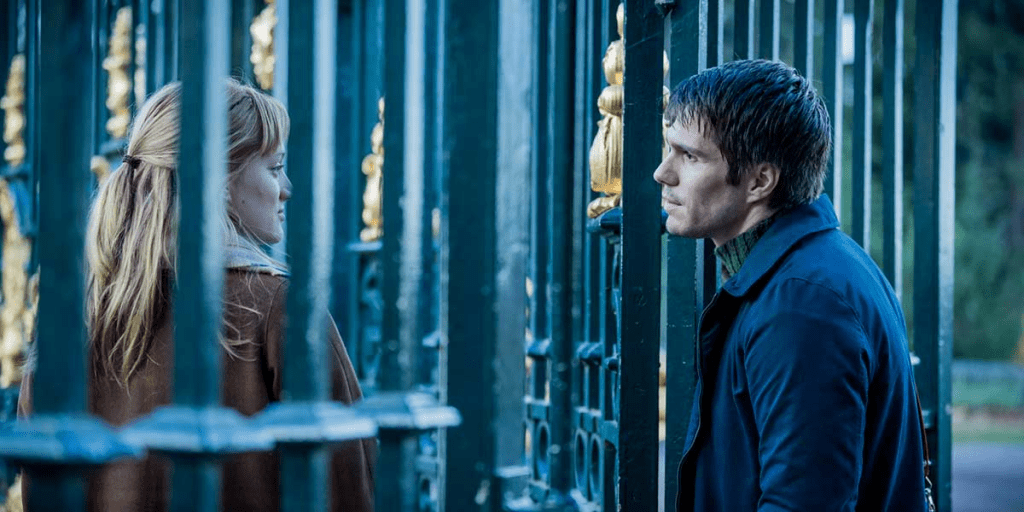

“Two Pianos“, directed by Arnaud Desplechin (“Kings and Queens“), for all its differences, falls into a somewhat similar trap. The young virtuoso at its center — played with skill by François Civil (“Mon Inconnue“) — is magnetic, almost too much so. He’s a man whose brilliance and beauty draw everyone in, including the camera. He’s irresistible to everyone, no matter how poorly he behaves. An alcoholic yet still musically brilliant, even when hungover, he’s painted by the director as so fragile we can’t help but be entranced. Yet we watch him humiliate, seduce, and abandon with the same tumultuous precision he brings to the keyboard, and it makes us step back.

The film never quite dares to question him. His genius excuses all; his suffering is treated as sacred. The supporting cast, especially his long-suffering partner, played impressively by Nadia Tereszkiewicz (“Rosalie“) and his older mentor, beautifully portrayed by Charlotte Rampling (“Swimming Pool“), who tries to rescue him; both are extraordinary, grounding the film with the emotional realism its protagonist so desperately lacks.

Shot with a burnished, melancholy precision by cinematographer Paul Guilhaume (“Emilia Pérez“), “Two Pianos” shimmers with reflective surfaces — concert stages, rain-slicked streets, mirrors, and glass — all of which double the protagonist’s obsession with his own reflection. Desplechin folds in a faintly surreal mystery, when the pianist becomes convinced he’s seen his younger self playing in a Paris park, only to discover the child is actually his son, born from an affair with his best friend’s wife. The revelation lands with the force of a Greek tragedy — self-love curdling into self-recognition — though, like much in “Two Pianos“, the film is so enamored with its own romantic melancholy that the shock never fully connects to our emotional core.

What makes both “Hedda” and “Two Pianos” so compelling, and so frustrating, is how self-aware they seem to be about narcissism, and yet how easily they reproduce it and ask us to join in. They are, in a sense, mirrors: beautifully lit, immaculately composed, but reflecting only themselves. As cinema, they’re seductive; as psychology, they’re evasive. Both directors are too enamored with their leads to fully diagnose them. And so, what could have been portraits of pathology become love letters to self-absorption.

Perhaps that’s the irony of these two films at TIFF — surrounded by cinematic beauty, we’re reminded how much art still believes that beauty redeems everything. But it doesn’t. Both “Hedda” and “Two Pianos” left me thinking less about their protagonists’ supposed genius or torment, and more about the quiet, steady humanity of the people orbiting them — the ones who we see clearly, love honestly, and yet rarely walk away.

[…] (Die My Love)Renate Reinsve (Sentimental Value)Julia Roberts (After the Hunt)Tessa Thompson (Hedda)Eva Victor (Sorry, […]

LikeLike