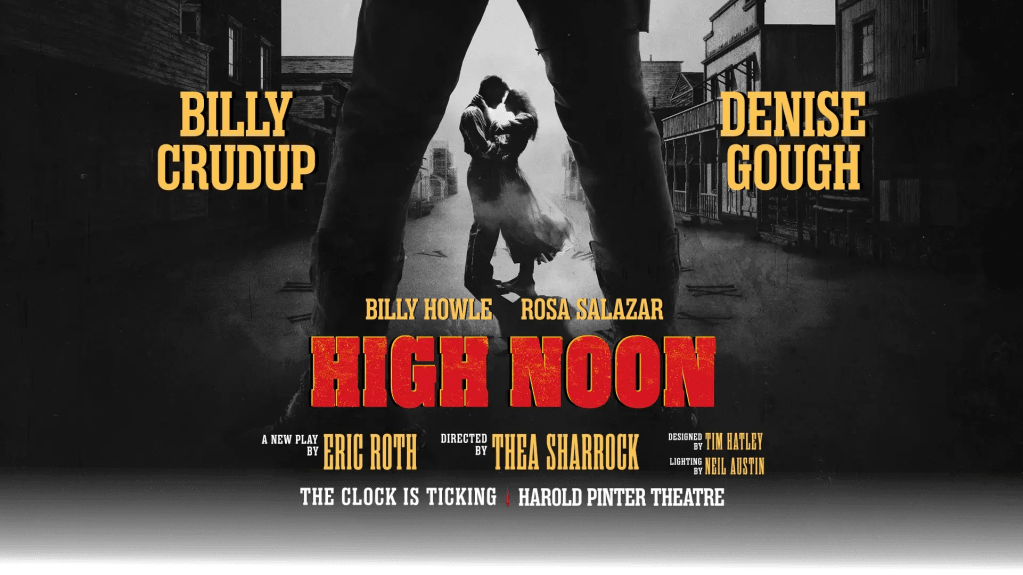

The London UK Theatre Review: High Noon

By Ross

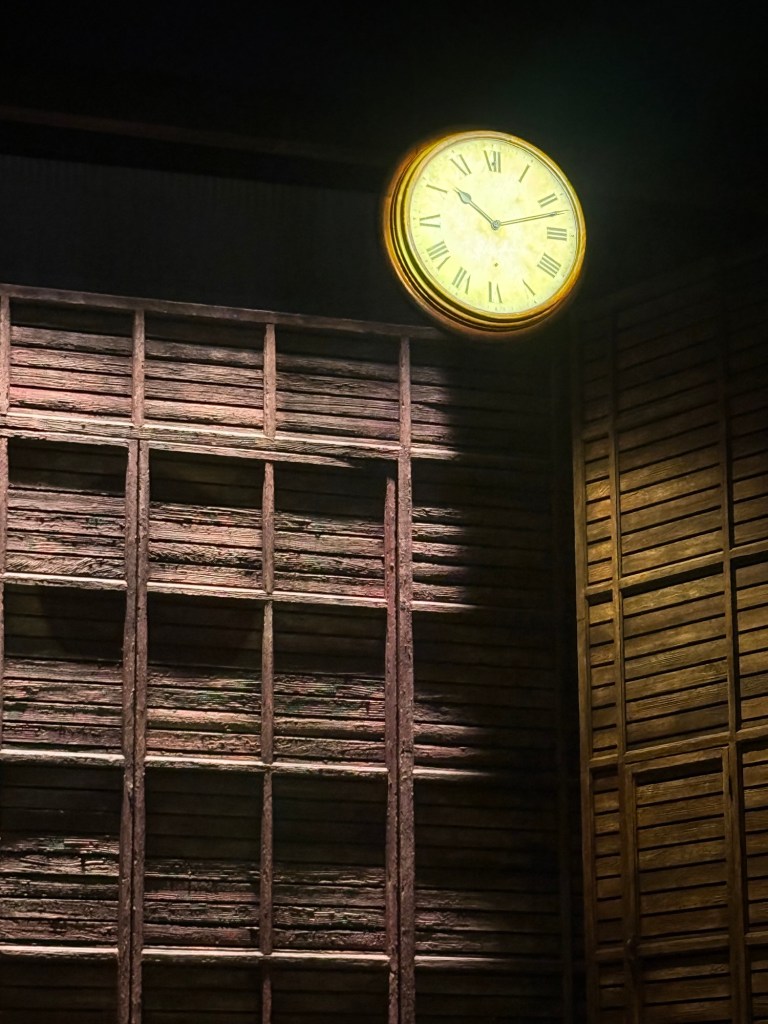

An old-fashioned clock is stationed over the stage like a warning, or a stopwatch, counting down the minutes until High Noon strikes and Marshal Will Kane must face the returning outlaw Frank Miller, arriving on the noon train. It’s a potent image, borrowed from one of cinema’s most elegant narrative devices: time itself as antagonist. In writer Eric Roth’s new stage adaptation of High Noon, now playing at the Harold Pinter Theatre, that clock is always visible, always ticking, always noting the passing of time. Yet for all the insistence of its presence, the production rarely manages to make us feel its pressure, or its urgency.

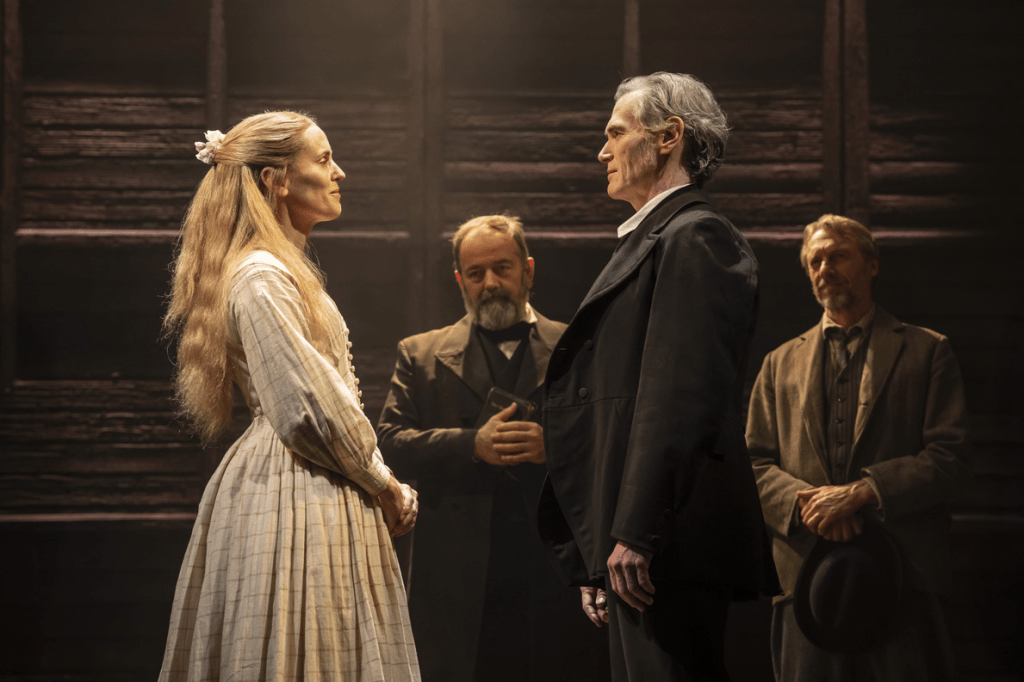

What does land decisively is the acting. Billy Crudup (“The Morning Show”; Vineyard’s Harry Clarke) gives Will Kane a quiet, weathered authority, grounding the role in moral exhaustion rather than swagger. Denise Gough (West End/Broadway’s Angels in America), as his wife Amy, supplies the evening’s moral code and emotional backbone. She fascinatingly stands firm in her belief system, navigating the character’s pacifism and terror with fierce clarity. Their scenes together are the production’s most alive moments, suggesting the human cost of courage more convincingly than the script ever articulates it.

The hypnotic Rosa Salazar (“Play Dirty“) is a standout as the surprise bar owner, Helen Ramirez, bringing intelligence and heat to a role that understands the town’s hypocrisy long before the men do. The interaction between Salazar’s Helen and Gough’s Amy is one of the most compelling and stimulating moments within the play, where differing perspectives on love and loyalty are particularly enlightening. Misha Handley (“The Woman in Black“) is genuinely affecting as Johnny, the young man under Helen’s maternal protection, though the script ultimately abandons him just as he begins to claim some captivating space within the story. Across the cast, performances are stronger than the writing demands of them, with actors supplying more motivation, texture, and emotional logic than the play has given, where the text often does not.

The central problem with this High Noon lies squarely in Roth’s script. Heavy-handed and curiously inert, it lacks the sharp drive forward required for a real-time thriller. Motivations are thinly sketched, conflicts asserted rather than earned. Even moments of confrontation, such as Billy Howle’s Harvey Pell squaring off against his former mentor Kane, feel dramatically obligatory rather than emotionally inevitable. The actors strain to locate inner necessity where the structure provides only narrative requirement, and while Crudup and Gough succeed in creating a center of gravity, they are too often left delivering lines that circle ideas without sharpening them.

Still, the thematic resonance is unmistakable, if blunt. Watching a town refuse to stand beside a clearly righteous figure, hoping instead that evil will pass them by if they remain silent, lands with uncomfortable familiarity. The parallels to contemporary American politics are not subtle, nor are they meant to be: collective cowardice, moral abdication, and the danger of assuming that someone else will do the hard work of resistance. These ideas connect most powerfully in individual moments rather than in the play’s overall shape, but they do connect, and sometimes sharply.

Director Thea Sharrock’s staging is handsome and ambitious, with the set and costume design by Tim Hatley (Broadway’s Life of Pi) and the lighting by Neil Austin (Broadway’s Harry Potter…) crafting a bleak, open landscape that evokes both isolation and exposure. Yet the much-touted ticking-clock device never translates into escalating tension. Unlike the recent West End/Broadway Oedipus, where each passing second raises the temperature and ignites the air, High Noon remains curiously flat. The clock counts down, but the dramatic stakes do not compound. The production gestures toward fear rather than generating it, and scenes drift where they should detonate.

The music, drawing on songs by Bruce Springsteen and Ry Cooder, provides an effective emotional undercurrent, particularly for the female characters. However, its repeated phrases occasionally tip from haunting into lazy insistence. In the end, this High Noon is admirable in intent and often compelling in performance, but undermined by a script that mistakes significance for urgency. The clock keeps ticking, but the explosion never quite comes, leaving a production that wants desperately to be a wake-up call, yet struggles to jolt itself out of a stalled afternoon slumber.