The Broadway Theatre Review: MTC’s Bug

By Ross

She stands, staring into the light coming through her hotel room door, left ajar, not from a place of security, but one of anxious disturbance. The stillness is deafening, as is the quiet desperation that lives inside this woman’s body. The way she, Agnes White, curls herself up on the chair and how her body moves around the room, snatching up a continuously ringing phone and screaming into the static as if she is waiting for an invasion. “Gerry, is that you?” she barks, snarling into the receiver in hopes that her anger will scare her ex-husband away. She counts her cash, wondering if she is plotting an escape. Is it physical, removing herself from this room and this existence, or something more medicinal? But then we see the pipe, and the manner in which she is numbing herself. And we understand the the picture and the framing on the wall.

This is going to be a different mode of travel, one that is as desperate as any, and we can’t help but sit up, waiting for the danger to arrive, just like her. But the danger does not come from where we expect. Her ex is there, for sure, striking her hard across the face and taking her money because he wants it, but where the real attack comes from is somewhere else, unexpected, from that quiet stranger who innocently enters the space, invited in like a vampire, without anyone really seeing the sharp teeth he has, including his own self.

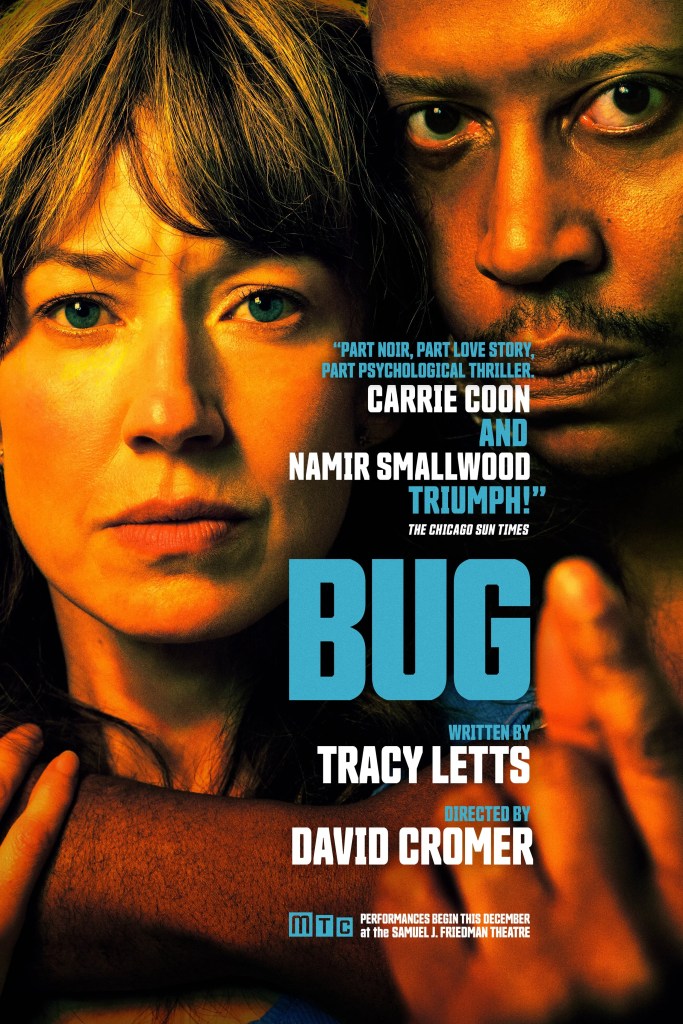

“I pick up on things,” he says, pulling her and all of us into Tracy Letts’ hypnotic Bug, which burrowed its way into Manhattan Theatre Club’s Samuel J. Friedman Theatre on Broadway with unnerving precision and an almost unbearable intimacy. Directed with meticulous restraint by David Cromer (Roundabout’s The Counter), this Steppenwolf production refuses to play it easy; it unleashes a corrosive logic of loneliness and shared delusion. What begins as a tentative connection between two damaged people in a rundown Oklahoma motel room becomes a study in how desperation will bend reality to avoid abandonment over and over again, against all odds.

The meticulous Carrie Coon captures the essence of Agnes White in a way that is nothing short of astonishing. Her performance is a masterclass in emotional self-erasure and physical restraint, a woman so starved for connection that she will override her own senses, instincts, and history to keep the quiet and lonely Peter Evans in the room. Coon (“The Gilded Age“; NYTW’s Mary Jane) allows us to witness Agnes choosing abstract belief in small steps as an act of survival. This is not foolishness, in her mind, but a requirement. She listens, absorbs, and adapts, even as Peter’s conspiratorial worldview grows increasingly unhinged.

Agnes is even willing to discard her most loyal and grounding presence, R.C., played with aching clarity by Jennifer Engstrom (KC Rep’s Angels in America). That choice speaks volumes about how seductive shared madness can be when the alternative is isolation. Engstrom’s astonishing physicality prowls the room like a guard dog, instinctively positioning herself between Agnes and danger. There is a hope that through sheer vigilance, she can protect her friend from both the violent ex hovering outside and the man Agnes herself has invited in. Her stance communicates far more about R.C.’s loyalty and fear than anything she says aloud.

Namir Smallwood (Broadway’s Pass Over) as Peter is completely hypnotic, frightening, and oddly soft and tender. He never plays Peter as a caricature of paranoia, but as a man whose belief system has become the only structure holding him together, and we find ourselves digging in with him even as we recognize the danger. His nemesis, Randall Arney’s Dr. Sweet, is a deliberately persuasive door to either world, playing the caregiver and the sly seducer like a two-sided coin thrown high in the air. Together with Agnes’s abusive ex-husband, Jerry, played solidly by Steve Key (Barrow Street’s The Effect) outside the door, the two further complicate Agnes’ reality, reinforcing in different ways the sense that truth is flexible if safety is conditional. This is a world where authority figures cannot be relied upon to rescue you, and where the most dangerous thing in the room is feeling seen by the wrong person.

“We’ll never really be safe again,” they tell each other in more ways than one, and the production’s design elements deepen that psychological descent with remarkable control. Takeshi Kata’s set steadily transforms the motel room into a sealed pressure chamber plastered with fear and disturbance, raising the emotional and existential stakes with every rotating shift. Sarah Laux’s costumes, Heather Gilbert’s lighting, and Josh Schmidt’s sound design remain finely tuned to the escalation, guiding us into Peter’s infestation paranoia while daring us to feel it ourselves. Even understanding the diagnosis and recognizing the warning signs, we are pulled into the sensation, scratching at the edges of our belief system, right alongside these desperate characters.

The most devastating moments come not from overt violence, but from Agnes’ active participation in Peter’s growing conspiracy. Watching her connect imaginary dots in real time is debilitating, heartbreaking, and deeply disturbing. The need to be protected and chosen becomes so overwhelming that she dives headfirst into danger, fully aware of the cost. If anything, the presence of an intermission slightly disrupts the momentum, as the play’s power lies in its relentless forward motion toward collapse. Still, Bug remains a gripping and compassionate examination of mental illness, desire, and the terrifying comfort of believing together. This Broadway premiere confirms the play’s haunting cult status, and offers an infestation that lingers long after the room goes dark.