The Toronto Theatre Review: TIFT’s Company

By Ross

Two men enter quietly. One takes his place at the piano, the other at center stage. As a radio dial searches for a familiar frequency, snippets of static and melody drift in and out. Fragments of loneliness are carried in the night air, as Stephen Sondheim’s Company finally tunes itself into focus. With only a piano and violin supplying the score, Talk Is Free Theatre’s production at The Theatre Centre begins with an intimacy that feels deliciously deliberate and deeply inviting. The city hums around these characters, demanding to be heard, as couples gather and Bobby answers their plea for engagement with a simple yes. And in that solidly crafted celebration, this production, helmed by director Dylan Trowbridge (TIFT’s Cock), brings into focus this splendid stripped-back revival that feels warm, immediate, and decisively alive.

When the cast gathers to sing a rousing “Happy Birthday,” circling Bobby with an imaginary cake whose candles cannot be blown out, the image lands with precision. We know we are in good hands as the couples fan out around him in star formation, affectionate and suffocating all at once, reinforcing the central question of the evening: when you have friends like these, what else are you supposed to want?

Originally opening on Broadway in 1970, Company, with music and lyrics by Sondheim and a book by George Furth, was a radical rethinking of what a musical could be. Discarding linear narrative for a series of vignettes, it examined marriage, commitment, and emotional paralysis through sharp humor, magnificent lyrics, and aching honesty. Hal Prince’s original production, with Michael Bennett’s kinetic staging, helped define the musical as a portrait of modern adulthood rather than romantic fantasy. More than fifty years later, Talk Is Free Theatre honors that lineage by trusting the material and allowing its emotional architecture to speak clearly.

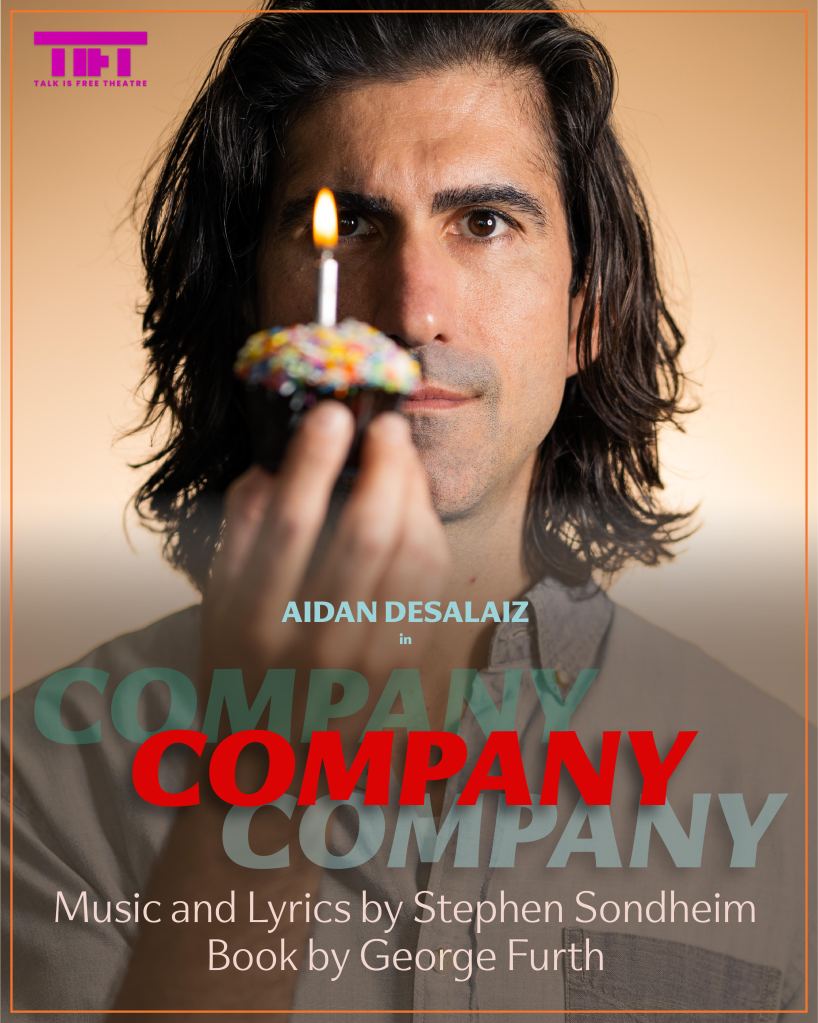

At the center of this production is the fascinating Aidan DeSalaiz as Bobby, a man circling his thirty-fifth birthday while quietly interrogating his resistance to commitment. DeSalaiz (Stratford’s Spamalot) brings thoughtful engagement and emotional intelligence to the role, grounding Bobby’s turmoil with thoughtful sincerity. While his vocals lack the rugged power of some past interpreters, including Raúl Esparza’s ferocious turn in the 2006 Broadway revival, his performance finds emotional truth within his vulnerability and intent. His Bobby feels present, searching, and very much surrounded by choices he cannot yet make.

Encircled on all sides are his “good and crazy” friends and lovers, Bobby moves through a series of entwined vignettes rather than a traditional plot, each one punctuated by impressive songs that compress entire emotional arcs into a handful of precise minutes. Under Trowbridge’s direction, the production’s intention is clear: to keep the evening in constant motion, buoyant and alert to the shifting rhythms of intimacy and avoidance. That momentum largely pays off thanks to a richly inhabited ensemble, most purely realized in a buoyant, playfully engaged rendition of “The Little Things You Do Together,” where the cast’s ease with one another becomes its own quiet argument for companionship.

The male partners are particularly well cast and confidently sung, with Michael Torontow’s Larry commanding attention whenever he enters the space, even when seated beside Gabi Epstein’s formidable Joanne. Epstein, in her own right, is a magnetic force, delivering “The Ladies Who Lunch” with ferocity, charisma, and a sharp sense of authority that refuses to soften its bite. Sydney Cochrane’s Amy expertly tears through “Not Getting Married,” slowly finding her own self along the way under Stephan Ermel’s crisp music direction. Maggie Walters brings endearing innocence and unexpected poignancy to her April — yes, April — especially in her quietly devastating butterfly story. Moments like these remind us how deftly Company balances comedy with emotional exposure when it trusts its performers and its songs to carry the weight.

Where the production occasionally falters is not in ambition, but in a reluctance to occasionally let that material breathe. The choreography by Rohan Dhupar (Bad Hats’ Narnia) sometimes pushes too insistently at moments already rich with meaning, naming an emotional intention that the music has already articulated. This is most evident during Marta’s “Another Hundred People,” where Sierra Holder delivers a strong, clear performance that deserves more visual restraint. Marta only fully claims her presence after being lost on the stairs in the dark when she is finally allowed to stand high above the fray on a bench, illuminated by the inconsistent lighting of Jeff Pybus (Shaw’s La Vie en Rose). There, she elevates the song’s loneliness more effectively than all that unrequired movement that surrounds and distracts. When intention and effect do align, however, the results are exhilarating. “Side by Side by Side” snaps into thrilling cohesion, the ensemble locking together with tight precision. A rotating couch at center stage, part of Varvara Evchuk’s flexible set and costume design, becomes a recurring symbol of Bobby’s restless interior life, though its audible mechanics occasionally pull focus away rather than deepen meaning.

That tension between trust and overstatement also surfaces in smaller scenes. The episode with the tightly wound Jenny and gentle David, crisply played by Kirsten Russell and Richard Lam, finds its footing when Robert introduces marijuana into their living room, loosening the exchange just enough for the couple’s scrutiny to turn inward. When Kathy (an endearing Madelyn Kriese), Marta (Holder), and April (Walters) sweep in Andrews Sisters-style for “You Could Drive a Person Crazy,” the song itself does the heavy lifting, the performers crackling with energy even as the costuming slightly undersells the number’s comic precision. Elsewhere, certain directorial choices raise more questions than clarity, most notably an unexpected kiss following Peter (Jeff Irving) and Susan’s (a delightful Jamie McRoberts) Mexico divorce anecdote. It is a moment designed to jolt the audience into attention, and it succeeds on that level. But its emotional logic remains elusive, leaving us alert to a possibility without a clear sense of what insight it is meant to unlock.

Having seen Company across decades and continents, from the Donmar framework to Marianne Elliott’s revelatory 2018 West End and then the 2021 Broadway reimagining that re-centered the show around a female Bobbie, this Toronto production feels like a respectful and confident return to the musical’s essential questions. Sondheim once remarked that Company dared to hold a mirror up to its audience’s own anxieties rather than offering escape, and that remains its enduring power because it trusts its audience to sit with discomfort rather than resolve it. Talk Is Free Theatre’s production is at its strongest when it extends that same trust to the material. It does not reinvent the musical, but it does something equally valuable and considered. It listens closely, performs honestly, and reminds us why Company continues to speak so incisively about connection, fear, and the courage required simply to be alive.