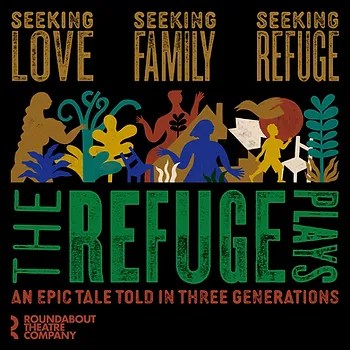

The Off-Broadway Theatre Review: Roundabout Theatre Company’s The Refuge Plays

By Ross

Epic is the word, and fascinating. Even after three and a half hours. Making us lean in almost from the very moment they all file out, crawling into their beds with a lantern lighting the bedroom way for a man in white to kiss them sweetly. It’s a solid set-up, this forehead pre-wake-up kiss. It floats forward like the elusive smoke from a hand-me-down pipe filled with the smell of vastness and glorious otherworldliness. The energy burns strong, giving off a compelling edge to the world premiere of The Refuge Plays, a three-part generational drama, ushered forward by the Roundabout Theatre Company at their off-Broadway space, the Laura Pels Theatre. And no wonder it feels heavy-haunted; this tale of one Black family over seventy years in the deep woods of southern Illinois, as the ghostly figure brings forth some deadly news to his surviving wife. He tells her, not-so-secretly, that she will be joining him soon, within the next twenty-four hours. And as written with humor and heart by Nathan Alan Davis (Nat Turner in Jerusalem), The Refuge Plays dynamically opens the window to a world of generational trauma and the search for safety. And it seems they have found this place, rooted in unity and security; a refuge in the woods that will keep this American family engaged and entangled, with a few surprises around the corner, slipping in unknowingly in need of something far and remote from the outside world. A place without an address where no one can find them or bring them harm.

As directed with a calm yet direct edge by Patricia McGregor (Roundabout’s Ugly Lies the Bone), The Refuge Plays unwinds itself backward, spanning seventy years and three generations over three one-act plays and three ghosts in white over three and a half hours, with two intermissions. The first unpacking takes place in the present, or something akin to the present, as time and period seem a bit blurry and unspecified. When a woman named Gail, played compassionately by understudy Rokia Shearin (American Stage’s The Royale) in a part usually played by Jessica Frances Dukes (Roundabout’s Trouble in Mind), wakes up and begins the day by smoking her “dead-ass husband’s pipe” in hopes of creating some peace for herself in the morning. It’s an engaging first moment, one of many throughout this lovingly constructed play, and house.

It’s clear that in this wide-open, long, but magical play, the first white figure is that previously mentioned husband who goes by the name of Walking Man, gloriously embodied by Jon Michael Hill (Broadway’s Pass Over). He was killed by a cow, if you can believe it (and you will as he talks us through his demise later on), and now he pays frequent compassionate visits to his wife and the other members of this four-generation clan living under that very small roof. He kisses them with love and care; his daughter, Joy, beautifully portrayed by Ngozi Anyanwu (Vineyard’s Good Grief), his grandson, Ha-Ha, delightfully played by JJ Wynder (HBO Max’s “That Damn Michael Che“), and Walking Man’s difficult and complaining hard mother, Grandma Early, dynamically embodied by the fascinatingly good Nicole Ari Parker (Broadway’s A Streetcar Named Desire; Fox’s “Empire“), the family matriarch and the one, as it turns out, who will be walking us through these woods, back in time, in hopes of finding some meaning and deliverance.

With Gail knowing that she will die within the next day, The Refuge Plays starts its trek through the complications of the world they all live in, and these equally difficult family dynamics. Grandma Early holds little love for the obliging and loving wife of her deceased son, saying of Gail, in all the bluntness of the world, “There’s some people in life, no matter how good they try to be, you just ain’t never gonna like ’em. You’ve decided.” And we see it as clear as day. There is some epic story, one that revolves around the day she arrived at the house in the woods, with something that should have been Early’s by right. Where that conflict originates from, well, we get a hint. But that’s a “long long story that I ain’t gonna start right now.” Yet, we know it will be coming, and after we meet a surprising arrival, played delightfully by Mallori Taylor Johnson (FX’s “Kindred“) escaping or searching for something (maybe both things – and chips), we secretly hope all will be explained in due time. We just have to be wait in the woods with them all and be patient.

The second part of this American “family play” takes us one step back, with a very alive young Walking Man (Hill) out back of that very same house of the now much younger Early, one that we are told with deliberation was built by Early’s husband, Crazy Eddie, tenderly well played by Daniel J. Watts (Broadway’s Tina). Some of the framework of this family, this house, and their union has been built and laid out in the first act, but now we are given a view through the trees and a different vantage point of Mother Early. She’s as feisty as ever, spiking at her son with “Do you think you just made a point? Smiling like you think you did?“. It’s a clever motherly jab that is felt strong and true by the young and sensual Walking Man. He is the ultimate wanderer, getting lost wherever he goes, looking for answers to questions that aren’t that clear even to him. As played by the compelling Hill, this wandering Walking Man is as alive as one could be, but complicated on the inside. “Sounds to me like you’ve been a few places,” he is told by his flamboyant but adoring (and adorable) Uncle Dax, played true and fabulous by Lance Coadie Williams (Public/Broadway’s Sweat), “but you got to learn to pay attention to what you see.”

Walking Man yearns hard for something, while forever trying to find a light for that same pipe we were first introduced to earlier (and later) on. Dax’s character, while being an utter joy to watch and listen to, is out of place in this familial drama, rolling in, finding them water, talking about running off to Paris like “Jimmy Baldwin“, but, in a way, his main ‘raison d’être‘ is to introduce the young Walking Man to this elderly couple in white who keeps showing up wanting to speak to him. But only if Mother Early isn’t around. It turns out that these two souls, who are infinitely afraid of Early, are the ghosts of Early’s parents, played with an earthy presence by solid Jerome Preston Bates (Broadway’s Stick Fly) and the heavenly Lizan Mitchell (NYTW’s The Half-God of Rainfall). But the turning point comes near the end of this entanglement, when a woman arrives, unconsciously seeking refuge in a safe space, and discovers the seemingly lost, handsome Walking Man. It’s at that point that we start understanding what this spot in the woods, and what this fascinating play, is really all about. And we can’t help but continue to lean in.

The structuring of the third part starts off with almost everything, but a tree, stripped away, thanks to the very fine set design work by Arnulfo Maldonado (Broadway’s A Strange Loop), with compelling costuming by Emilio Sosa (Broadway’s Good Night, Oscar), distinct lighting by Stacey Derosier (O’Henry’s Uncle Vanya), and organic original music and sound design by Marc Anthony Thompson (A Huey P. Newton Story). It’s definitely earlier in this tale. Long before the house was a structure and a home. Early moves around that tree as if it were her own flesh, blood, and roots. She’s been breathing and surviving out here for a long time, she tells Crazy Eddie, who has driven up in his truck filled with food and drink for the runaway Early. He has left his world behind, not that it was such a great one, it seems. But he had an illogical calling to go looking for her after she disappeared, and he just had to find her.

And find her, he did, but he also discovered another survivor wrapped in a blanket and protected by something akin to a scared mama wolf at the foot of a bear cave. With a fourth unseen spirit hanging around keeping them there together, the two circle each other tentatively, wondering if they can find some faith in the other. Early doesn’t trust this man’s arrival, even though he’s bearing gifts. There’s so much trauma peppered in that “crisp” air, and a strong hunger for something to believe in. They both, in a way, are seeking some sort of refuge in the woods, from a society that wants to hurt them. She with a hammer and a sharp word to keep her and her baby, Walking Man, safe and protected. He with his gentle openness and a bag of stolen food. The world has already inflicted so much hurt and damage on Eddie, but the pain that Early is trying to escape is much more vivid without it even being dutifully examined (like Eddie’s legs) and unpacked.

They, by the grace of some god, have found a place to come together, in pain and in some sort of loving need. And maybe because of some chips “for, like, emotional emergencies,” as explained earlier by Symphony, an equal wanderer who showed up with Ha-Ha later (and earlier) on. The play beautifully digs itself into the roots of that tree, unpacking and processing decades and generations of trauma and hurt. Maybe a bit too slowly, but with loving details and dimensions that might have been lost if we ran backward too fast and too furiously. In that coming together, the safety these wanderers are seeking is in this place (and Plays) of The Refuge, where they can discover themselves from inside that stick-circled space of security in the woods. Next to a large tree and an unseen well of water and poetic goodness.

[…] Jagged Little Pill), exact lighting by Stacey Derosier (Roundabout’s The Refuge Plays), and an intimate solid sound design by Darron L West (Public’s Coal Country). Page, once […]

LikeLike

[…] of Our Teeth), lighting designers Jane Cox (2ST’s Appropriate) and Stacey Derosier (RTC’s The Refuge Plays), and sound designer Palmer Hefferan (Broadway’s Just For Us). But his death ignites the […]

LikeLike

[…] Nicole Ari Parker – The Refuge Plays […]

LikeLike

[…] Page, All the Devils Are Here: How Shakespeare Invented The VillainNicole Ari Parker, The Refuge PlaysJim Parsons, Mother PlaySarah Paulson, AppropriateSarah Pidgeon, StereophonicAubrey […]

LikeLike

[…] Page, All the Devils Are Here: How Shakespeare Invented The VillainNicole Ari Parker, The Refuge PlaysJim Parsons, Mother PlaySarah Pidgeon, StereophonicAubrey Plaza, Danny and The Deep […]

LikeLike

[…] defined costuming by Kaye Voyce (LCT’s Uncle Vanya), lighting by Stacey Derosier (RTC’s The Refuge Plays), sound by Palmer Hefferan (LCT’s The Skin of Our Teeth), and special effects by Jeremy […]

LikeLike

[…] February 25, 2025Opening: March 17, 2025Starring: LaTanya Richardson Jackson, Harry Lennix, Jon Michael Hill, Glenn Davis, Alana Arenas, Kara YoungWriter: Branden Jacobs-JenkinsDirector: Phylicia RashadAbout: […]

LikeLike