The London Theatre Review: Dr. Semmelweis

By Ross

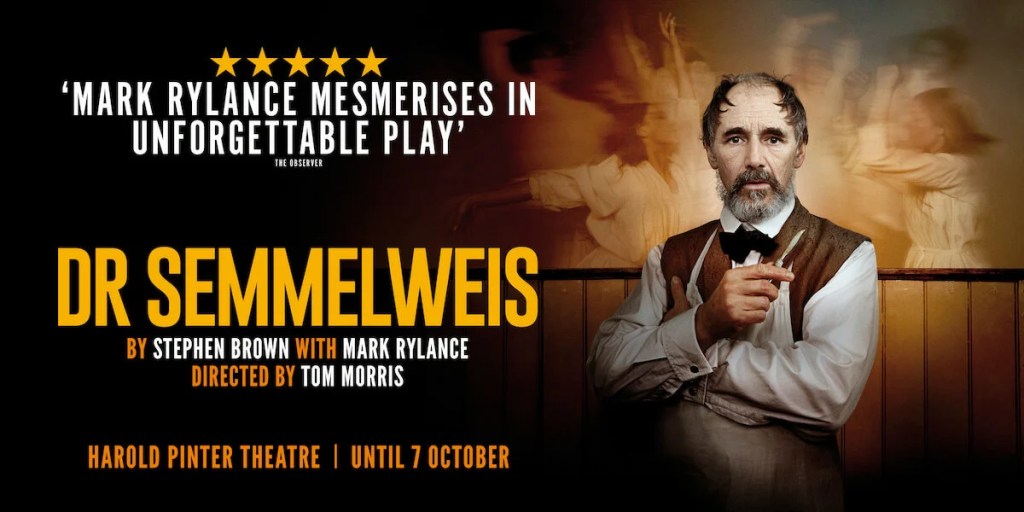

Music floats in, all around us, from all sides. Beautiful stringed instruments are played by secretive musicians standing there amongst us in the aisle at the Harold Pinter Theatre, London. It pulls on us, this music, into the play’s realm within an instant, and then they appear, in pools of white light, haunting the stage and the mind of the central force in Dr. Semmelweis, a new play written with an intense sense of purpose by Stephen Brown (Occupational Hazards) with the help of its star, Mark Rylance.

But the unraveling begins first with a game, one that he is very good at, unlike the game he plays in real life. “Come back,” she says. “It’s your move.” And we can’t help but lean in to the loving dynamic, looking with intensity as he gives her “time to rethink your move.” It’s a completely enticing first moment, funny and engaging, showcasing Rylance as the lead character, Dr. Ignaz Semmelweis, being a bit of the arrogant creature that he is, but also giving us some of the tender engagement and respect that exists inside of his marriage. We like this man, in a way, even as he displays some of his more complicated natures. Personality traits that draw him into power struggles and ego conflicts of his own making. They play out time and time again, maybe too much, for this play to handle, but as hauntingly directed by Tom Morris (Bristol Old Vic’s Touching the Void), this new play based on an original idea by Rylance doesn’t disappoint, even when it drags itself forward a bit too coldly. Yet, the play, originally developed by the National Theatre Studio and produced by Bristol Old Vic, spins a fascinating web, albeit a bit slowly, unpacking the story of Semmelweis, the man “who discovered something“, but fell victim to the harshness of the world. His own demons never stop hovering nearby though, haunting his mind and formulating his sometimes overzealous response, one that leads him down a path towards oblivion, not recognition.

Much like that circle of ghostly souls who also fell victim to a system that didn’t want to take responsibility for their own blindness, the play tries to unwrap a history most complex and disheartening with Mark Rylance (Broadway’s Farinelli and the King; “Don’t Look Up“) taking on the title character in the brilliant way that he does. His eccentricity expands the form, breathing life into a figure who speaks the truth, but many times gets himself into situations before he thinks his way through, and much of the time to his own detriment. Dr. Ignaz Semmelweis, as history likes to note, was a man ahead of his time, unearthing ideas that we now have a hard time not understanding why he and his theories weren’t embraced. He was living and working in a world that hadn’t yet uncovered the concepts of the invisible killers; bacteria or viruses; something we know a little bit more about now than any of us did a number of years ago, before the pandemic when this play was first being developed. Stepping back, the tale of Semmelweis’s unraveling guides us in a way that makes us understand both sides, even as we judge and shake our collective heads at the medical establishment whose own arrogance forced them to dismiss an outcome that seems so obvious to us, particularly now in the world we inhabit.

Don’t forget the truth, the spirits suggest, dancing quietly all around in the dark void, wordlessly screaming in pain from infection and deaths that could have been prevented. If only they would have listened, we think, but back in the day, before the discovery of antibiotics, the systems of medicine were rife with male privilege, snobbery, arrogance, and exclusivity. To stand up and be heard, in the 19th Century, required more than just an idea. It required all sorts of things that Dr. Semmelweis didn’t possess, even if his ideas held concrete truths based on scientific research. Yet, he did have the courage to see the truth before him, and know that “the end is only the beginning“. That’s at the core of this compelling new play, and after the last few years, it carries a different weight than it would have if the play had made it to the stage even five years prior.

“It’s not a miracle, but science,” and as unpacked by this fabulously talented crew of artists, Dr. Semmelweis navigates the two frameworks of time with a magnificent duality, drawing us into the darkness of these dancing women and the politics of the medical community that Semmelweis does battle with. He’s not a comfortable man, nor is he a politician, by nature, leaving him to go to battle with only the facts and a few ideas, which, it seems, were not enough. But the confrontation of theory against power gives us a great conflictual dance to take in, and on that sparse inventive set, designed thoughtfully and artistically by Ti Green (TFANA’s The Emperor)- who also designed the costumes – friction echoes through the space like spirits never letting us forget their pain. Reminiscent of a viewing theatre of an operating room, the stage construction allows the ghostly mothers to emerge almost silently from the darkness, basking in the hot contrasting timely shades and tones of light designed by Richard Howell (Donmar/Public’s Privacy) to music created by Adrian Sutton (West End/Broadway’s Angels in America), pulling at our hearts and minds with equal power.

It’s a provocative hypnotic visual, taking us willingly into the deep, dark chasm of pain and death that engulfs the central figure, and pushes him toward madness. The play unpacks Semmelweis’s drive and inner unconventional thinking that ultimately overwhelm him and some of his trusted cohorts with the remorseful sadness of dismissal and banishment. Rylance, mischievously, pulls us into his past and his utter self-absorption and single-mindedness, which make it so difficult for him to tolerate those who question and negate his thinking. Death dances around them all, but it pushes the hardest on Semmelweis’s sense of causality and understanding. Why are the death rates so different in the maternity ward of the hospital Semmelweis is working in, and why are the midwives doing a better job keeping these mothers alive after they give birth? It’s a factual complication that drives Semmelweis to act, impulsively and without approval, but within the thoughtfulness of a scientist, he sets up a scientific system to truly understand the discrepancy. And he finds his way into the problem, maybe not to the exact explanation, which, in a way, is his downfall. But he does uncover a process that actually helps save lives, and the numbers prove it.

The play excels in exploring the inner unconsciousness of Dr. Semmelweis’s pain and guilt, with Rylance leading the charge. Within that uncovering, he has filled the play to overflowing with talented actors giving it their all, finding worlds of relevance in the processed thinking of those scientists and doctors at the time. It also echoes the distrust that is, sadly, alive and well in our politics today around COVID and vaccinations. It plays with Semmelweis’s unconventionally, steadfastly unpacking the power dynamics of that time, in 19th-Century Vienna, when doctors arrogantly pushed back hard on any idea that pointed the finger of blame towards their own actions. Semmelweis knew that not washing their hands before working with patients was causing the death of numerous mothers, the ones that were forced into the doctors’ wing, rather than the safer midwife arena. He was like a dog searching for a bone, unable to focus on anything else but the problem, invisible, standing before him. And he knew in his heart of hearts, that new windows were not the solution to their problems.

Pulled into the past relentlessly by the dead dancers, the play jumps around in time, exploring life as a doctor from Hungary, working in a 19th-century maternity ward for the poorer class of women. He discovered the antiseptic formula that would save lives, particularly those of the impoverished mothers who showed up at the door of this hospital needing help with the birthing of their child, if only the medical establishment would hear him out and believe in his theory. But he didn’t have a way with words, causing numerous high-powered egos to be damaged, and ultimately his banishment from that hospital was insured. He was dismissed and ridiculed, removing himself to Hungary where his unwritten thesis, although never taken seriously in his lifetime, resulted in many women who were in his care surviving the birthing process at a much higher rate than any other hospital in Europe.

The history is compelling, especially knowing that the man ultimately died in an asylum without ever being recognized for his contribution to the field and to humanity; dying of sepsis, the very thing he worked so hard to save his patients from. Rylance excels in the part, but it’s no surprise as it seems this play was his passion project; to tell this sad, almost Shakespearean tale of tragedy and to embody the man himself on stage. The cast around him: namely Roseanna Anderson (Marja Seidel/ Baroness Maria-Teresa), Zoe Arshamian (Dance Ensemble), Joshua Ben-Tovim (Hospital Porter/ Death), Ewan Black (Franz Arneth), Chrissy Brooke (Lisa Elstein), Megumi Eda (Aiko Eda), Suzy Halstead (Violet-May Blackledge), Felix Hayes (Ferdinand von Hebra), Pauline McLynn (Anna Müller), Jude Owusu (Jakob Kolletschka), Oxana Panchenko (Polina Nagy), Millie Thomas (Agnes Barta), Max Westwell (Hospital Porter/ Death), Amanda Wilkin (Maria Semmelweis), Alan Williams (Johann Klein), Daniel York Loh (Karl von Rokitansky), Patricia Zhou (Antonette du Boisson) and Helen Belbin (Widwife Caroline Flint); do their job exceptionally well, filling in the space around them with their excellence and complete engagement.

They all form a web of intricacies that develop and push the story forward, especially Wilkin (Soho Theatre’s Shedding a Skin) as his wife, Maria, and all the men who float around Semmelweis in this all-male world of medicine, treating females as a theoretical exercise and learning tool. More importantly, there is Pauline McLynn (Park Theatre’s Daisy Pulls It Off) as the straight-talking nurse Anna Muller, who becomes Semmelweis’s true and loyal partner in his underground experimentation. Her tragedy, like his, at the hands of the establishment and, most powerful, Semmelweis, unleashes one of the stronger waves of emotion that this sometimes coolly delivered play elicits.

The thematic structuring is beautifully rendered, casting a dark poetic layer of movement and grief over the arena, thanks to the compelling choreography of Antonia Franceschi (Soho Theatre’s Up From The Waste) and her troupe of ten dynamic ballet dancers and the all-women Salome String Quartet [Haim Choi (Music Director/ Violin 1), Coco Inman (Violin 2), Kasia Zimińska (Viola) and Shizuku Tatsuno (Cello)], that guides us deep inside the chaotic mind of Semmelweis and gives light to his many problematic mannerisms, particularly his unhinged anger and lack of restraint. Both of which get worse and worse with each scene.

Dr. Semmelweis, the play, like the man himself, is as much of a complication as it is compelling, driving forward madly and deeply, almost obsessively, forgetting at times to engage in the more basic of human emotions. The play is visually compelling, finding connection more in the corners of the space than in the center. It sometimes makes the journey a bit of a slog, but it is fascinating in the end, as Semmelweis’s ideas predated those of Joseph Lister and Louis Pasteur. And although he wasn’t able to articulate the reasonings, possibly one of the stronger reasons that his theories weren’t taken seriously, along with his pushy arrogance and unpredictability on the matter, the man and the doctor remain a true pioneer, even though his genius was never immortalized like those others. Maybe that’s what Rylance was trying to correct. And he did, in his own way, with a grand visual and intellectually stimulating piece of theatre and dance. I just wish it had a bit more emotionality at its core, to really pull us into this Shakespearean tragedy, and make us feel the force of this undeniably good play.

[…] West End’s “Dr. Semmelweis” Has the Entertaining Courage to Truly Deliver the Trut… […]

LikeLike

[…] by Scott Pask (Broadway’s Shucked), with solid lighting by Richard Howell (West End’s Dr. Semmelweis) and sound design by Autograph’s Niamh Gaffney & Terry Jardine. With vigorously […]

LikeLike

[…] by madness, yet it is the murderer Bosola, played forcefully by Jude Owusu (West End’s Dr. Semmelweis) who finds a contemplative foundation of understanding, forging resistance alongside these women […]

LikeLike